World Bank sanctions challenge overseas opportunities for Chinese enterprises

Excerpt from CCG new book focusing on outbound investment by Chinese companies against a saturating domestic market.

Hi, this is Jia Yuxuan from Beijing bringing you an excerpt from The Challenge of “Going Out”: Chinese Experiences in Outbound Investment, part of the Chinese Enterprise Globalization Series published by Springer and the Center for China and Globalization (CCG). It is edited Henry Huiyao Wang, Founder and President of CCG and Mabel Lu Miao, Co-Founder and Secretary-General of CCG.

The book encapsulates the phrase "zou chu qu" or "going out," highlighting the shift in Chinese companies' strategies from a focus on domestic growth to seeking opportunities in global markets. The introduction of the book discusses the significant growth of China since its accession to the WTO in 2001 and its integration into the global economy over the last two decades. It also the complexities and challenges faced by Chinese companies as they navigate the global business environment, dealing with challenges ranging from protectionist policies and geopolitical issues to the overall global economic slowdown in recent years.

The book is divided into five main parts, each focusing on different aspects of outbound investment and the "going out" process.

The first section, titled Policy and Environment, addresses the policies that shape and influence the outbound investment strategies of Chinese companies. This part includes discussions on the Chinese government's guidelines and incentives for enterprises "going out," as well as the regulatory landscape that these companies encounter in foreign markets. It also covers how international trade agreements and geopolitical shifts impact Chinese outward investments.

The second part, Underlying Trends and Influencing Factors, explores the driving forces behind the surge in Chinese outbound investments. It examines economic, technological, and market trends that have emboldened Chinese enterprises to seek opportunities abroad. The section also explores the strategic considerations of Chinese companies, such as accessing new markets, acquiring technology and brand assets, and diversifying holdings.

The third part, Legal and Compliance Concerns, is also a crucial part consideration for Chinese enterprises and looks at the legal challenges and compliance issues that Chinese companies face when investing overseas. It examines how to navigate different legal systems, understand international trade laws, and ensure compliance with regulations in areas like environmental protection, labor rights, and corporate governance.

The fourth part, Opportunities and Risks in Developed Economies, focuses on developed markets and analyzes the opportunities and challenges in these environments. It looks at how Chinese companies adapt to more competitive and regulated markets, manage cultural and business practice differences, and deal with issues such as market saturation and higher operational costs.

The final part, Notable “Going Out” Case Studies, puts theory into practice by presenting case studies of successful Chinese enterprises. This section analyzes successful companies like Geely, which acquired Volvo, and Fuyao Group, known for its investment and integration into the US market. These case studies not only highlight successes but also examine the challenges these companies faced and how they overcame them.

Each section of the book is structured to provide a comprehensive understanding of the complexities and nuances of Chinese outbound investment, making it an essential resource for business leaders, policymakers, and academics interested in international business and economic relations.

This excerpted chapter, abridged due to space limitations, is authored by Jihua Ding, Deputy Director of Beijing New Century Academy on Transnational Companies.

Ding's chapter highlights the worrying trend of Chinese companies facing debarment and sanctions from the World Bank and other Multilateral Development Banks, primarily due to fraudulent activities violating procurement guidelines. Ding attributes these cases to Chinese enterprises undertaking projects in countries and industries with a high risk of corruption and their lack of compliance awareness and knowledge of the World Bank sanctions system. The chapter concludes with Ding offering compliance advice to address these challenges.

Establishing a Compliance Management System to Manage the Risk of the World Bank Sanctions

When participating in projects funded by Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) such as the World Bank (WB), enterprises may be sanctioned if they fail to comply with the relevant compliance requirements. If this happens, the enterprises are prohibited from participating in any WB-funded projects and may even face sanctions from other MDBs, thereby restricting it from participating in MDB-funded projects.

At the beginning of the 21st century, a number of Chinese enterprises and individuals were debarred by the WB. As Chinese companies undertook few WB-funded projects, and the influence of the companies and individuals involved held minimal influence at the time, they did not attract the business community’s attention. However, this has changed. In recent years, the WB has debarred an increasing number of Chinese companies. Some of these enterprises are influential in the inter- national arena, resulting in the WB’s sanctions system attracting widespread attention from the business community.

It is worth noting that there is a high degree of geographical overlap between the distribution of WB-funded projects and the locations of “Belt and Road” projects; Chinese enterprises are involved in a large number of WB-funded projects in these regions. If these enterprises are de-barred by the WB for non-compliance, they will not be allowed to participate in projects funded by the WB or other MDBs. These enterprises may also become targets of other governments, enterprises and financial institutions, or face unfavorable cooperation.

Overall Situation of World Bank Sanctions on Chinese Enterprises

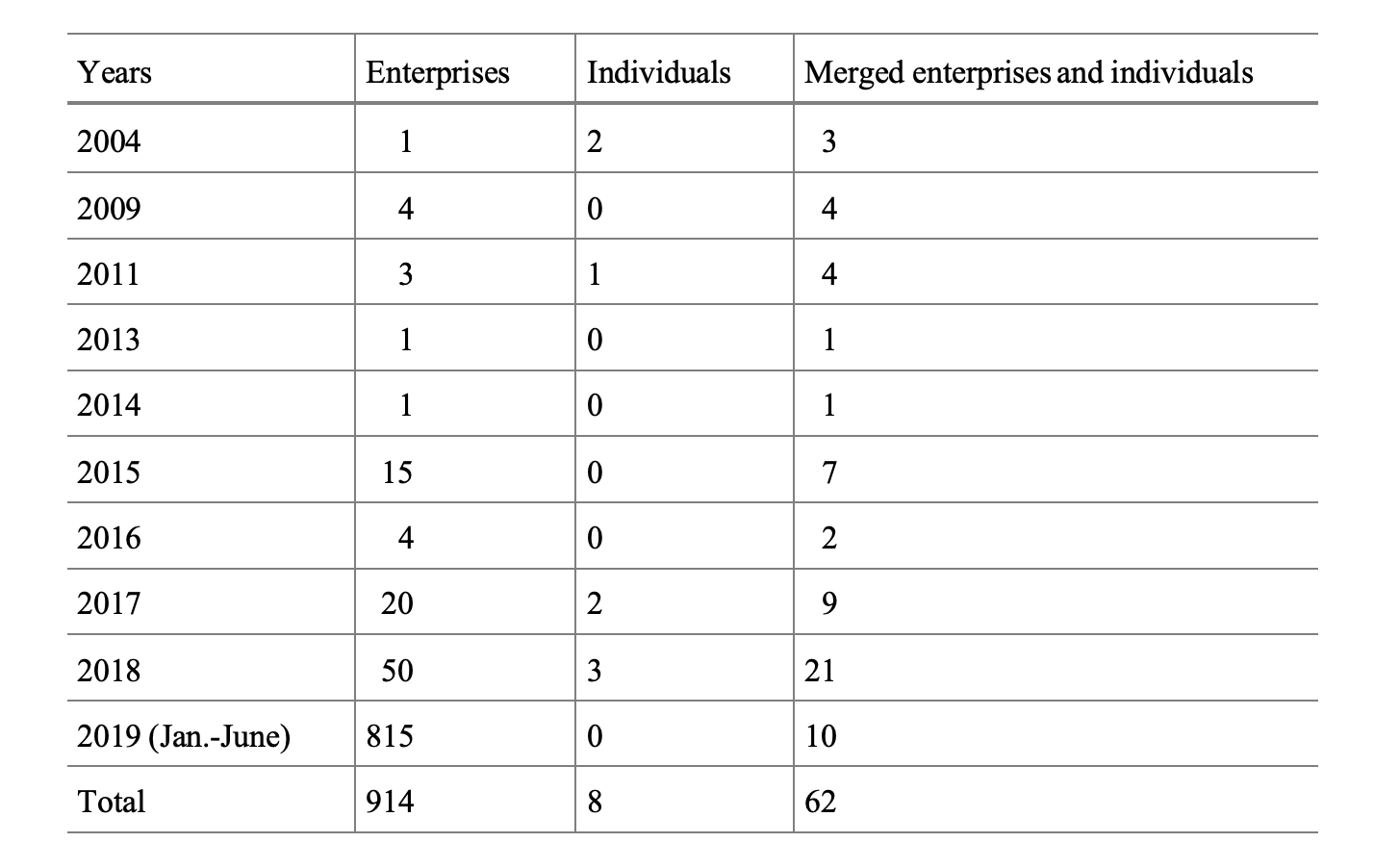

As of June 12, 2019, there were 54 Chinese companies sanctioned by the WB. In some cases where an enterprise directly or indirectly controls multiple enterprises, which are also affected, this number would increase to 914 if all were included. In addition, the WB has also sanctioned eight individuals. 18 enterprises and four individuals on the sanctions list were cross-debarred by the WB for being sanctioned by other international development banks. Two enterprises were sanctioned by the African Development Bank; 15 enterprises and two individuals were sanctioned by the Asian Development Bank; and the Inter-American Development Bank sanctioned one enterprise and one individual.

Of course, the above statistics were obtained solely based on the WB’s publicly sanctioned list and it should be noted that the WB has also notified the Chinese government of violations by some Chinese companies for misconduct that are currently under investigation. The list of these companies, however, is not publicly available. Some companies have reached settlements with the WB on their own initiative or participated in its voluntary disclosure program before initiating investigations. The exact number of enterprises involved in these two groups is not available to the public, but it should be within the single digits when combined with relevant information disclosed in previous years.

More than 99% of the sanctioned enterprises are engaged in infrastructure and engineering projects. The WB often sanctions these enterprises for bidding non- compliance, which includes providing incorrect information or falsifying documents, both of which violate the anti-fraud provisions of the WB’s procurement guidelines.

Recent Shocking Cases of Companies Sanctioned by the WB

On May 14, 2019, the World Bank announced its decision to impose debarment sanctions on Sieyuan Electric Co., Ltd., a company based in Shanghai. The reason for this was that the enterprise falsified past contractual documents to meet the contract requirements when participating in the procurement process for a WB-funded power project contract in Ghana. The WB considered this action fraudulent and in violation of its procurement guidelines. The enterprise subsequently settled with the WB. The company and its 28 affiliated subsidiaries were disbarred for 15 months as part of the settlement agreement.

Less than a month after the above-mentioned company was sanctioned, on June 5, 2019, the WB announced that it had debarred the China Railway Construction Corporation Ltd (CRCC), which is a Chinese state-owned construction and engineering company. This debarment was also applied to its wholly-owned subsidiaries (i.e., China Railway 23rd Bureau Group Co., Ltd. (CR23) and China Railway Construction Corporation (International) Limited (CRCC International)) and the CRCC’s 730 controlled affiliates simultaneously. The sheer number of sanctioned subsidiaries within a single enterprise is shocking and broke the WB’s previous record, which was set when it sanctioned SNC-Lavalin Group Inc. and its 133 subsidiaries in 2013. The company was sanctioned because of its misconduct during the pre-qualification and bidding process for the East-West Highway Corridor Improvement Project in Georgia (preparing and submitting information that misrepresented the personnel and equipment of CR23 and the experience of other entities in its group belonging to CRCC).

According to the WB’s Administrative Sanctions System and the WB’s Procurement Guidelines, these actions are considered fraudulent practices. After a long period of communication, the company cooperated with the WB and reached a settlement agreement, which shortened the disqualification period. After their nine-month debarment, CRCC, CR23, CRCC International, and its 730 controlled affiliates were conditionally non-debarred for 24 months. As a condition for the release of sanctions, the companies and their affiliates had to commit to enhancing their integrity compliance programs to be consistent with the principles set out in the World Bank Group Integrity Compliance Guidelines. The company also had to commit to fully cooperating with the World Bank Group Integrity Vice Presidency. They would again be eligible to participate in WB-financed projects during this period as long as they complied with their obligations under the settlement agreement. If they did not, the conditional non-debarment would revert to debarment with conditional release.

Why Chinese Enterprises were sanctioned by the WB?

Since 2015, the number of Chinese enterprises sanctioned by the WB has continuously increased. As more Chinese enterprises are “going out”, this trend is likely to continue. There are several reasons why Chinese companies are sanctioned by the WB:

WB projects are generally in countries with a high risk of corruption. Studies have shown that the countries that receive the most funding from the WB (underdeveloped and developing countries in the world) are also considered to be at higher risk for corruption. Transparency International’s (TI) annual Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) monitors global corruption risks, scoring more than one hundred countries and territories from 0 to 100, and countries that score below 50 are considered to have serious corruption problems. In FY2014, the Integrity Vice Presidency of the WB surveyed and reported on 32 countries, 19 of which ranked 110th or lower in TI’s 2013 Corruption Perceptions Index (177 countries), and more than 60% of the complaints were suspected to be related to corruption and embezzlement.

Also, around 50% of the WB’s funds are spent on infrastructure projects in the energy, transportation, water, and IT sectors. These sectors are often high compliance risk areas, which the WB monitors. In 2008, a WB investigation found that companies had produced false qualifications to build infrastructure projects in East Asia and pharmaceutical companies in South Asia. The investigation found evidence of large- scale corporate cartel bidding in contracts of WB projects. In 2009, WB projects had the highest number of newly established cases with the health, transport and water sectors. A Transparency International poll rated construction as the most corruption- prone sector, and a survey of international companies showed that companies in the construction sector were more likely to lose contracts to bribery than companies in any other sector. In 2010, global road projects received an all-time high of US$9 billion in WB loans, accounting for 15% of WB’s total lending for the year. The Integrity Vice Presidency’s 2011 analysis of past sanctioned and pending sanctioned cases in the road sector found that WB-funded projects were not immune. The WB has accused approximately 25% of the companies involved in 500-odd WB-financed projects of one or more allegations of fraud, corruption or both.

Companies do not know enough about the WB sanctions system, the design of which is based on the US legal system. This system acts as an institutional guarantee to ensure that its procurement policies are undertaken correctly.

In procurement contracts for WB projects, the companies involved in bidding and providing services are required by contract to comply with its procurement policies. Generally speaking, only companies that participate in WB projects will take the time to understand the relevant policies, and those that do not participate in WB projects will not. However, based on past cases and the actions of Chinese companies that the WB has sanctioned, these enterprises did not take enough time to understand the sanctions system. Instead, they simply decided to not undertake said projects after being sanctioned.

Government, media, and society also fail to pay enough attention to such cases, which is also an important reason why domestic enterprises do not attach enough importance to the sanctions system. In recent years, as China’s enterprises have begun to go global, many of them have participated in WB-financed projects. However, most failed to thoroughly understand or pay enough attention to the sanctions system, resulting in unknowingly breaking the rules. There are also cases where cultural differences have led to different understandings of procurement policies, resulting in misconduct and consequent sanctions. Such companies can significantly mitigate the impct of sanctions if they seek professional legal advice.

Corporate compliance awareness is generally weak. When participating in WB projects, some enterprises may not realise that behavior considered acceptable in their home country is not necessarily appropriate when operating in other countries. In looking at companies previously sanctioned by the WB, some seem to have made simple mistakes (e.g., forging bid documents, signatures, official seals) or over- looked conflicts of interest (using qualifications or performance of the parent or sister company as their own) and other forms of non-compliance. As a result, the WB has sanctioned companies for not complying with the WB’s contractual requirements during the construction phase or project completion.

State-owned enterprises face greater compliance risks. In 2014, the WB became concerned that state-owned enterprises (SOEs) were already taking on a growing proportion of its funded projects and becoming involved in many social development projects. In several countries, SOEs are the targets of a relatively high proportion of complaints and investigations requests received by the Integrity Vice Presidency of WB, making up a third of the WB’s sanctions list. Some SOEs involved in projects have conflicts of interest when parent and subsidiary companies bid for the same contract or commit fraud by using each other’s experience and qualifications. The integrity and compliance survey results show that SOEs engage in tacit collusion in domestic projects, lack clear rules, standards and transparency, have non-transparent management and supervision structures, resulting in corruption and project losses. In recent years, the WB has focused on proposing solutions to the risks of SOE participation in projects, not only by working with SOEs, but also by discussing with relevant government departments and adjusting the World Bank Group Integrity Compliance Guidelines based on the unique characteristics of SOEs.

Suggestions for Enterprises to Manage the Risk of World Bank Sanctions

Given the global trend of strengthening corporate compliance, the compliance program advocated by both the WB and countries to prevent and combat corruption is becoming a global standard.

Targeted Prevention of Compliance Risks

The following situations in a bid may be considered red flags by the WB and companies should be aware of them: (1) Complaints from bidders and other parties (including WB staff, competi- tors, contractors or other bidders, government officials, employees of NGOs, and other MDBs); (2) Numerous contracts with values just under procurement thresholds (tailoring a contract to fall just under the procurement threshold or seemingly arbitrarily splitting a contract into several more minor contracts to avoid higher-level review or competitive bidding); (3) Unusual bid patterns such as bid-rigging and quotation exception; (4) Seemingly inflated fees from agents or prices of goods to intermediaries or suppliers; (5) Suspicious bidder; (6) Lowest bidder not selected; (7) Unjustified and/or repeated sole source awards; (8) Unjustified changes in contract terms and value; (9) After the contract has been signed and during implementation, contractors often propose different orders; (10) Goods/services are of low quality or not delivered.

Improving Understanding of the WB Sanctions System

It is important to note that some enterprises may believe that the Integrity Vice Presidency does not have compulsory investigative powers over enterprises, which lead to confrontation with the WB’s investigation. Senior US experts designed the WB’s investigation and sanction procedures and investigation methods, which means that approaches are based on the experience of the US Department of Justice and European Union law enforcement agencies, providing the WB with a diverse range of investigation methods. Furthermore, the WB can collect relevant information from multiple chan- nels by establishing a global information network through long-term cooperation with government departments and financial institutions of countries.

In addition, the investigative team is highly experienced, staffed not only by former government investigators but also by lawyers and other intelligence experts. Therefore, whenever the Integrity Vice Presidency initiates an investigation, and a company receives corresponding notification documents, it must be taken seriously. While professionally responding to the investigation, a comprehensive self-examination should also be undertaken. If found guilty of non-compliance, it is best to quickly settle with the WB to ensure the most favourable outcome for the company.

Strengthen Compliance Risk Awareness and Make Prudent Decisions

When undertaking projects supported by the WB or other MDBs, all enterprises must assess the compliance risk of the project location in detail and make prudent decisions. If they are unaware of compliance risks, or if they prepare to follow domestic business habits or usual practices to participate in the bidding. Suppose they do not comprehensively assess the compliance risks exposed by the project. In that case, enterprises must strengthen their compliance training as soon as possible and engage experienced compliance experts or lawyers who are well versed in compliance to participate in related projects and provide advice and opinions. In this way, enter- prises can make correct decisions and protect their business results in the complex, changing, and strongly regulated international business environment.

Promoting the Creation of Enterprise Compliance Management Systems

1)Establish a compliance management system.This includes establishing a compliance management organization, formulating various compliance management policies that respond to external laws and regulations and internationally accepted rules in the course of business, and institutionalizing compliance training, compliance performance assessment, and self-monitoring systems. Senior management should also lead by example in developing and adhering to a culture of compliance.

2)Ensure the effectiveness of compliance management systems. To ensure that the compliance management system is well designed and can be effectively implemented, the following steps are crucial: make decisions based on compliance risk; provide sufficient and appropriate resources; ensure that the compliance management department reports to the board of directors independently; integrate compliance function into other departments; internally evaluate the independence of compliance; monitor compliance in high-risk areas such as third parties and high-risk ares such as bidding, and provide training to business partners with high compliance risk; establish effective reporting and monitoring channels, and carry out targeted compliance training and communication for all staff.