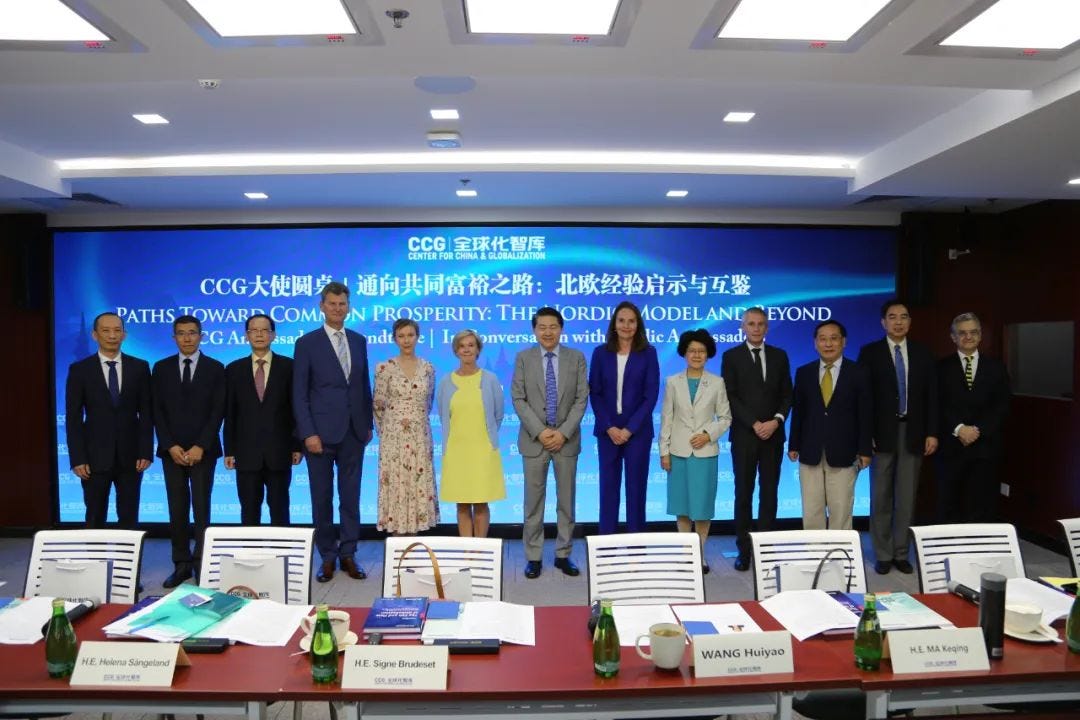

Nordic Ambassadors' presentations on the Nordic Model & Common Prosperity at CCG

Helena Sångeland of Sweden, Leena-Kaisa Mikkola of Finland, Signe Brudeset of Norway, Thomas Østrup Møller of Denmark, & Thorir Ibsen of Iceland.

On June 7, 2023 CCG hosted five Nordic ambassadors in China for a roundtable discussion named Paths Towards Common Prosperity: The Nordic Model and Beyond.

The public event was broadcasted via video in China by CCG. Apart from CCG’s widespread social media presence, Chinese outlets including China Agricultural University, The Beijing News, Beijing Radio and Television, Zhejiang Provincial 潮新闻, and Hong Kong-based, Chinese-targeting Phonenix TV carried reports.

(Credit: Phonenix TV)

Chinese guests also spoke at the event. You can also watch the video recording here.

Below are the presentations of the five ambassadors, respectively.

Presentation by H.E. Helena Sångeland, Ambassador of Sweden to China

The topic of my intervention today is addressing the demographic challenges in Sweden from an economic perspective. When we talk about demographic challenges, over-population is still a major problem, and human population has grown beyond a sustainable means. We are consuming more resources than our planet can regenerate with devastating consequences, and this goes particularly for richer countries, like my own. More people mean an increased demand for food, water, housing, energy, house care, transportation and more, and all that consumption contributes to ecological degradation, and increase conflicts and a higher risk of large scale disasters like pandemics.

This is a very important topic - how to grow the world population in a sustainable way. But, the demographic challenge that I wish to talk about today is from an economic perspective, because many countries are grappling with lower birth rates, and aging populations, which increases costs to the economy, pressure on health services, competition for jobs, or decreased participation in the workforce, potentially less funding for young people, and an increased dependency ratio.

Population growth,,on the other hand, will lead a higher tax revenues, which can be spent on public goods, such as health care and education. By that token, it can be a good thing to have an increasing population. Sweden is just like our Nordic neighbors, one of the richest countries in the world, but we are also rich country whose population still grows, and ages, and this picture illustrates by year 2100, Sweden’s population is estimated to grow from today’s 10.5 million to 13.7 million, and in a Chinese perspective, that’s quite laughable, it’s the size of a fourth tier city in China, but it’s still growth.

Sweden is one of the few countries which will continue to grow, whereas others will decrease. Population growth in Sweden basically comes down to two factors: there is more births than deaths, and more people move to Sweden than move out. The policy challenge is to sustain a comparably higher degree of labor market participation, in order to support both our children and our elderly.

So what are the measures that Sweden has taken? In the 70s, which indeed was a decade of many reforms, we came to political consensus that we needed to create possibilities for women to both work and have family. The economy grew fast, and we needed all hands on deck, in our manufacturing sector and service industry. We also needed the population to keep on growing. So, what was introduced in the 1970s was a number of reforms, the provision of heavily subsidized childcare, equal for all. Municipalities have to provide for all children regardless of what hours their parents work, meaning provision of nighttime childcare for those who works as nurses and doctors and others who work nightshifts.

School is free so as to provide equal opportunities for all. There are also provisions of after school care, so that parents can work full time. Parental leave has gradually been increased to what we have today. A child can have one parent on paid leave for almost one and a half years, and with 80-90 percent of the leave paid. This parental leave must be shared, so at least one parent needs to take out a minimum of three months of the one and a half years. As you can see on this graph that fathers’ share of all parental leave days has increased tremendously.

For instance, when I get new staff at my embassy, young men in their 30s, if they are married or living with a partner, I can be assured that they will ask for six months of leave, although they are posted abroad and they are entitled to it. Just as mothers they are also entitled to take their leave for six months.

Universal child allowances are also provided and increase with the number of children that we have. Maternal and under-five mortality rates are low, and we have laws in place to hinder employer discrimination against pregnant women or to-be parents. We don’t discriminate against men or women, although it is the case that women still taken more parental leave than men, but the difference is shrinking.

What these reforms did, apart from allowing women and men to both work and have children, was that they transferred a lot of work from informal to the formal sector. Such as household chores have become jobs, which has a lot of spin-off effects like increased taxation and revenue. As a bonus, people don’t need to save up for day care, school, universities and elderly care.Thus they have more money and incentives to spend on consumption, in turn driving economic growth. Labor participation of women is today 71%. It’s still lower than that of men, which is 76%, but from an international perspective that’s rather high.

That’s not to say that we don’t have a lot of challenges, women still work more part time than men, they have lower salaries and higher unemployment, but we’ve come far during the past 50 years. Another factor affecting the labor force is how long we work; we are fortunate enough to have people living longer and healthier lives. Life expectancy has increased by almost 10 years for men and 7 years for women over the past 50 years, to 81 and 85 years respectively. But that also means that older people need to be supported financially for a longer time, unless they work longer, which exactly what they are doing in Sweden. The earliest you can retire today and to receive public pension is 63, and you have the right to choose to work until 69 and if you and your employer want, you can also continue longer than that.

Retirement age is constantly raised in pace with life expectancy and you have economic incentives for working as long as possible. The longer you work, the higher your pension will be. A remaining challenge is to improve working conditions for those carry out physically demanding occupational activities. For example, women who work as nurses, with long hours and heavy lifting of patients, we have to ensure that they have bodies and minds in shapes to enjoy retirement after 45 years of working.

And, of course, we also have immigration. Despite all our advances, the fertility rate in Sweden is 1.6 per women, and higher than that in most developed countries, but still not high enough to tip the scale in favor of population growth in the long run, even there are more babies born than those who die.

In the 60s and 70s, during our manufacturing boom, we would never have been able to make it without immigrants from our neighbour Finland and southern Europe. Today we have newly arrived refugees from war zones such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Eritrea and Ukraine, who are working in our services sector, taking care of our elderly and our children. Others are highly skilled immigrants advancing our technological and scientific development.

Although there is no lack of challenges, they largely contribute to how we have overcome the demographic challenge that so many countries meet at a certain stage of economic development. About 20% of Sweden’s population is born abroad (i.a. if you have two parents born abroad).I, for instance, am part of that immigrant population, because my parents were born abroad, they were born in Finland can came to Sweden to find a work in the 50s and 60s.

There is no one simple solution to address demographic challenges, but there are many measures can be taken that combined come a long way. Thank you very much.

H.E. Leena-Kaisa Mikkola, Ambassador of Finland to China

I will talk shortly about Finnish education system, and in particular about educational equality. I will concentrate on the Finnish system, but the issue of equality is very important for all of us in every country’s educational system.

During the last years, my country has often been in the headlines when it comes to quality education. According to many international surveys and studies, we have indeed done quite well in improving equal and quality education for all. But before highlighting the aspects of educational equality, let me start with a few words about historical background and the Finnish educational system in general. I will also address the issue of vocational education, which I think is essential when building the society for all, a society of equal opportunities.

It is perhaps of interest for you to know that Finland was among the last countries in Europe to make education compulsory. We became independent from centuries of Swedish and Russian rule in 1917, and the act concerning general compulsory education came into force in 1921. Schooling was common even before that, especially in the urban areas. However, in the countryside, where majority of Finns those days lived, schooling of children was less common. And this also relates to my own family background, my grandmother was born in a village in 1906 and she never went to school. The act from 1921 aimed to do away with the educational inequality between towns and countryside, and the idea of educational equality has remained one of the guiding principles in our education system ever since.

Equality consists of two dimensions - fairness and inclusion. Fairness means reducing the social-economic barriers, while inclusion is to ensure basic standards of education to all. We don’t live in a perfect world and it would be hypocritical to claim that we, or somebody else, has achieved complete equality through education. But while not perfect, I would say that Finland and other Nordic countries have done quite well. Finnish youth have universal and free access to education. Students’ gender or school’s language of instructions explains a very small part of the difference in skills during his or her educational path. Whether the student comes from the capital area or from the sparsely populated northern part of the country doesn’t make a real difference when evaluating skills, or academic achievements.

The successes that we have had didn’t happen overnight 102 years ago. It has taken many decades to achieve. There has been a series of reforms and responses also to changing economic needs. But through trial and error, Finland has built successes in education. Of course, broader societal factors have also been helpful. The overall commitment to equality, various welfare services, and the question of strong cultural trust have always been fundamental when developing our road. There has always been a kind of whole society approach, but what works for us, might not always be 100% copy pasted for others.

However, there are some ideas free for copying.

Firstly, education for all approach has been a hallmark for Finnish education policy since its onset. There has always been and there still is a broad political consensus to build public school system that will serve every student without costs. As a result, every Finn has subjective right to participate in quality schooling, cost free from early childhood education, all the way to obtaining a university diploma. The equality aspect is supported by investments, for example, in free school meals, free school rides, but also in investing in special education. The Finnish education system is in many ways very flexible. We know that students’ and pupils’ preferences change as they grow older. Education also needs to be able to respond to the fast-paced changes taking place in the labor market and the society. To allow for the necessary flexibility, there are no dead ends in our education system. A student entering and graduating a vocational school, for example, is still able to pursue later on a university level education. In recent years, efforts have been made to increase possibilities of personalizing studies, also already at the secondary education level, something that has been very much the case at the tertiary level of education.

Coming back to the culture of trust. At the primary and secondary level there are no ranking lists compiled of Finnish schools. The most important thing is the system of trust based on the qualified and committed educational staff. Educational policy development is to a large degree headed by professional educationalists, rather than politicians. Teaching is a sought-after career that people respect. Entry into that profession is quite hard - often only one out of 10 applicants is accepted into teachers’ training programs in the universities. But high standard of staff means also greater independence. The schools are able to supplement the national curriculum with locally important topics and independently decide how the teaching is carried out.

Now a couple more words about vocational education and why. We think good quality vocational education is not only about equality in education, but also about equal opportunities in the society as a whole. The development of Finland’s vocational education system has parts in our history. After the Second World War, Finland had to pay huge reparations to the Soviet Union, which were basically paid in goods, machinery, and ships, which we didn’t have. In order to have all these, we needed to significantly adjust our industrial production, which meant we needed a significant amount of skilled and qualified workers. That was the stepping-stone for our vocational education schools and appreciation of them. Nowadays, it takes about three years to get a vocational education degree. The training is to provide the necessary skills for working life. But not only that, the education also supports students’ growth as individuals and responsible members of the society. It is characteristic to the Finnish system that about half of the students choose vocational education as their secondary education.

To conclude, we Finns are quite pragmatic and levelheaded people. We are equally levelheaded and realistic about the challenges and problems facing our educational system. The picture is not always rosy and one must admit that in recent years, regional differences in educational inequality have grown. Also, the differences in the skills of students in different schools have grown somewhat. However, from an international perspective, the differences between schools and students are still quite moderate in Finland. When we see inequality, we take it very seriously, because it mirrors very much the equality in the society as a whole and also the social cohesion that makes us the happiest country in the world for the sixth time, which we value so much.

On a personal note, which explains educational thinking in Finland: during my previous postings, an educational expert from that country asked my older son, who was 15 at the time, what is the difference between the international school he attended at the time and the Finnish school he attended previously. My son explained that in this international school, we prepare for academic excellence, but in my Finnish school, we prepared for life.

Presentation by H.E. Signe Brudeset, Ambassador of Norway to China

Thank you, Dr. Wang. Dear Henry. Dear friends and colleagues.

First of all, I would like to say thank you very much to CCG for organizing this event. The topic of today, the Nordic model, generally refers to similarities in economic management, the organization of working life, focus on human rights and universal welfare services in the Nordic countries. But it is not a uniform model, but we share similarities.

We have a long tradition of valuable exchanges with Chinese and Nordic experts on our respective society models. In the late 1970s the Norwegian Ministry of Energy and the state-owned energy company Statoil shared experiences with CNOOC on management of the petroleum sector. Later we have had valuable exchanges on pension reform and gender equality. Now green financing is a topic.

Making relevant comparisons between China and the Nordic countries may not intuitively come across as relevant. The governance models are very different, the size of the populations are miles apart, but still, we share some of the same challenges – aging population, how to tune our education systems for the future labour market, how to avoid increased inequality. Today, I would like to touch on three topics central to the Norwegian governance model. The first is taxation, the second is management of petroleum resources and the third is state ownership.

If you want to understand how a country works, you should study its tax system. This is certainly true for Norway, where taxation issues are among the most hotly debated issues. And I believe the same is true for China. Recently, I had a look at a very interesting book called “Governing and Ruling: The political logic of taxation in China”. The author (Zhang Changdong) points to important dilemmas around taxation and economic growth, taxation and representation, as well as relationships between central versus regional and local authorities.

For Norway’s sake, our tax system is indispensable for securing strong government finances that fuel a sustainable welfare state. Openness and transparency in the tax system are essential values. Although Norway has been blessed with abundant petroleum and natural resources, our workforce is seen as the country’s most important resource. The main goal of the Norwegian employment policy is to ensure that as many people as possible participate in the labour market and contribute to society. This is a prerequisite for the sustainability of Norway’s welfare schemes; we must create value before we can share value.

A broad tax base founded on a high level of participation in the labor force is necessary to ensure sufficient revenue. But we also believe it promotes fair distribution, value creation, and work incentives. Tax revenues are also used to redistribute, and to reduce inequalities between people socially, economically, and geographically.

The Norwegian system and culture expect that all who are capable of participating in the labour market do so, and seek – through free training and education – to facilitate everyone’s inclusion in the workforce. Norway has thus a relatively high retirement age, normally 67 for both men and women. Norwegian policymakers are working for an inclusive labor market that makes it possible for men and women, immigrants, the young, the elderly, and people with disabilities to find gainful employment and continue working longer.

Our high labour market participation, together with a broad tax base, generates income to the state, which in turn can be redistributed for the common good of society. Again - we must create value before we can share value.

Making sure that those with the highest incomes and most wealth contribute most helps generate sufficient revenue and a fair tax burden, but it also fosters trust. Trust in our society is incredibly important.

Income, wealth, and opportunities are often unevenly distributed geographically. To even out these disparities, successive Norwegian governments have developed policies that promote geographical redistribution. Subsidies are offered to various industries located in the periphery, such as agriculture, where national food security is an important aim.

In general, today’s public welfare schemes in Norway include free healthcare (beyond a small deductible) and education, generous maternity and paternity leave, retirement and disability pensions, unemployment benefits, 100% sick pay, and other welfare services and benefits. In addition to ensuring a strong social safety net, the interaction between the welfare system and a well-functioning labour market with small wage gaps, has contributed to a high employment rate, low income inequality, a high degree of transparency, equal opportunities, and social trust.

Another important factor for a good and stable Norwegian economy has been responsible management of petroleum revenues.When oil and gas were discovered on the Norwegian continental shelf in 1969, it sparked discussions about how revenue should be handled in order to benefit all Norwegians, including future generations.

In 1990, Norway established a sovereign wealth fund, today known as the Government Pension Fund Global. The state’s revenues from oil and gas extraction are now kept in the fund, together with the returns on the fund’s investments. The fund’s statutes and investment rules are regulated by the Parliament and the organization of the fund is supervised by the Ministry of Finance. But the fund operates independently and free from political interference. The majority of investments are made in low-risk international equities and bonds. The current size of the fund is around $1.4 trillion, which makes it the second largest sovereign wealth fund in the world.

To avoid the so-called resource curse, we have established “the budgetary rule”, which says that “transfers from the fund to the central government budget shall, over time, follow the expected rate of return on the fund”. This is today estimated to about 3%. As significant emphasis is placed on evening out economic fluctuations and contributing to sound capacity utilization and low unemployment, the annual transfers may exceed 3% in difficult times and be well below that in normal times. The transfers are thus used in a counter-cyclical manner into the Norwegian economy. The fiscal policy framework has aimed to preserve the real value of the fund for the benefit of future generations. The revenues that we get today are not for generations today, but also for future Norwegians.

State ownership has also been an important tool for making sure that our common resources benefit all. Private ownership is, as a rule, preferred in Norway’s mixed market economy and direct state ownership requires a special justification. In the area of common resources, the state owns a higher share in the domains of energy and the extraction of natural resources, but private companies also participate in this sector and contribute to a competitive business environment.

It is, however, worth underlining that state-owned companies in Norway operate at an arms-length distance from the government, and are subject to the same rules and objectives as privately owned companies. The state can exercise its rights as a shareholder, but the company is managed and operated independently by its management personnel and board of directors. Typically, the government focuses on the rate of return with many state-owned companies listed on the stock exchange and include private shareholders as well.

Creating a perfect system for economic and social governance is nearly impossible, as most variations on any system have their advantages and disadvantages. Nevertheless, economic systems need to be well adapted to the changing situation in the countries that have adopted them, and a fair balance between competing ends and considerations must be found.

Although the Norwegian and Chinese systems and realities differ, we find it to be highly valuable to engage in discussions and experience sharing with Chinese counterparts on such issues. So – thank you very much again to CCG, my Nordic colleagues and the other distinguished participants. I look forward to further exchanges on these topics. Thank you!

Presentation by H.E. Thomas Østrup Møller, Ambassador of Denmark to China

The first thing that came into my mind when I heard about today’s topic was the concept of trust. Of course, trust is not inherently a Nordic idea, or a foreign concept in China. Nor is trust a concept with a single meaning. We can talk about several types of trust.

One type is individual trust, a trust in someone you already know. An evolutionary trait that most likely dates back to the primitive hunter-gatherer societies. If you were injured during a mammoth hunt, you could trust your small clan to care for you. This makes sense, and we all have family members that we trust dearly. Those who are close to you, you trust. Another type is institutional trust, your confidence in public bodies such as courts, police and the administration. I will get back to that in a bit.

But let me start by telling you about our take on trust in the Nordic countries. Although there may be variations, we trust each other – almost by default. This is a third kind - societal trust. This is trust in strangers you’ve never met before. And I believe that this is quite fundamental to the Nordic Model and Nordic way of life.

Let me give you an example. Many Danes will remember a story from 1997, when a Danish woman left her 14-month old daughter asleep in a baby carriage outside a coffee shop in New York City. The mother was sitting inside, and could see the baby through the window, so everything to her was in perfect order. But soon a concerned citizen called the police, who took the baby into custody and arrested the woman.

Luckily, she got off with a warning, and mother and child were soon reunited. Yet, if you’ve ever been to Denmark, you have without a doubt noticed there are many baby carriages outside local coffee shops. In Denmark, we routinely leave sleeping babies outside, without any direct supervision other than a sound recorder, so we can hear when they wake up. This is a very concrete example of societal trust. We simply trust others – people we’ve never met – enough to leave our children sleeping alone.

And this leads me back to institutional trust. We also have great trust in our government, legal system, police and administration. Don’t get me wrong, one of our favorite pastimes is complaining about politicians or the bureaucracy. But in the end, we generally trust them to do the right thing. And we trust that our public institutions and authorities act in a fair and impartial manner. Both societal trust and institutional trust is crucial to our welfare model. Denmark and the other Nordic countries are strong welfare states. This model relies on redistribution of tax revenues between strangers, not among people with mutual individual trust relations. Such a system doesn’t work if you don’t trust institutions to divide the cake fairly. And it doesn’t work if you don’t trust your neighbor enough to expect her to do her share.

In other words, this model means that everyone is expected to contribute and to have a sense of duty. But it also means that everyone is sure to receive care and help if anything happens to you. If you get sick or when you get old, you don’t have to worry about sick bills or whether your kids live close enough. You can trust the system to take care of you.

An added benefit of trust is that it lowers transaction costs in the economy. With trust, it’s easier to get things done. You don’t need to provide excessive legal hedging to foster joint action or to promote exchanges between economic agents. Some would argue that this is a significant part of the explanation of why Nordic welfare states are also fairly wealthy states. But why do we have such a high level of trust in Nordic countries? It’s not because we’re inherently different from everyone else.

I believe one reason is our political system. Through transparency, oversight and separations of powers, people trust that policy outcomes and the public administration is run in a fair way. Laws and rules are clearly defined and fairly and impartially implemented, no matter who you are or how much money you have in your bank account.

Another reason is the process by which we make laws. For instance, we have a very strong consultation mechanism for hearing public demands. This leads to a sense that rules are there to promote and protect the interests of every individual. We have a sense that following the rules is both in your own interest as well as the overall interest of society and the nation.

This doesn’t mean that we don’t, from time to time, experience irregularities among public authorities or politicians. But when cases like this happen, we deal with them through due process in a transparent manner. And the almost certain debate about the issue contributes to a sense that such problems are not allowed to take root. From the outside, our political system or debates in the public sphere about politics may seem disorderly, or even chaotic. Maybe you get the sense that our society is brimming with discontent and antagonism. But to us, debate – sometimes fierce debate – is seen as strength and a sign of a well-functioning, healthy system. As such, debate and diverse opinions don’t undermine the system. Rather, it actually contributes to trust in the system, and between all of us. Thank you.

Presentation by H.E. Thorir Ibsen, Ambassador of Iceland to China

I will devote my presentation to two observations.

Firstly, a general observation about the Nordic approach, and secondly a more specific observation about Iceland´s experience of sustainability.

As for the general observation, the Nordics are pragmatic. We avoid using strong words in our analysis of state-of-affairs. We believe that dramatized language is not helpful and in fact can be dangerous as it can encourage reactions and solutions that are neither useful nor peaceful.

Thus, instead of drawing up a dramatic picture of the challenges that the world community is facing, we approach these challenges in a pragmatic and analytical manner with a view to solving the problems.

As a Nordic, I thus take issue with such broad stroke generalization that we are living an era of crises.

We are certainly facing important challenges and changes. But we are not facing crisis, and certainly not multitude of crises. Our institutions, society and economy have not become dysfunctional. – And neither our societies nor the world order are at the brink of collapsing or being transformed into a new social or world order.

On the contrary, we have, at least in the Nordic countries and in Europe, efficient democratic governance that constantly address income disparity and other socioeconomic challenges through fiscal policy, the education system, health care and the welfare system.

We like diversity and we have a long-standing democratic tradition, institutions and independent media that foster cohesion through free and transparent political discussion.

We have decades of experience of resolving environmental problems. -- And we lead international cooperation to protect the environment and promote sustainable development.

And our security architecture, especially NATO has proven to be one of the most cohesive, capable and committed collective defensive alliance in the world. It safeguards our way of life, our freedoms, and our security. This has been especially important since Russia´s brutal and illegal invasion of Ukraine and war of aggression.

Turning to Iceland, and our experience of sustainability.

Iceland is an affluent, dynamic and democratic island country. We enjoy one of the highest living standards in the world, and as a Nordic country, Iceland has an egalitarian society, characterised by social inclusion, economic fairness and gender equality.

We built our affluence by adopting an open export-oriented market economy, and by developing the use of our natural resources into successful competitive export industries.

Relying as we do on our natural resources, we have learned the importance of protecting our environment and using our natural resources sustainably.

With sustainable resource management, we secure a more stable economy and long-term economic growth, as well as more equal distribution of economic rewards and social benefits.

Moreover, by focusing on sustainability, we unleashed innovation and growth of green practices and low carbon technologies that have brought Icelandic companies to the global market and indeed to China.

However, transforming the economy to sustainability is often easier said than done.

In our experience, for sustainable policy to be successful it must have a broad support among businesses and citizens alike. It must be justifiable and based on reason. And the policy and its implementation must be clear and transparent.

In other words, both businesses and citizens must understand the need for the policy, see their interest in implementing the policy, and be able to trust that its application is equitable, inclusive and just.

Thus, the policy must bring win-win for businesses and people as well as for the environment.

The regulatory framework must encourage sustainable business practices including through economic rewards. And the social and economic needs of communities must be met with secure employment.

Businesses and people must have ownership of the policy. That is, policies and measures must be developed with direct involvement of representatives of the relevant interest groups and stake-holders, and be subject to public consultations.

The policy must be justifiable and based on reason. Thus, the environmental measures and decisions related to the management of natural resource must be based on the best available scientific knowledge.

The policy and its implementation must be clear and transparent. Citizens and businesses must be able to see and verify that the sustainable policy is working and applied in a just and equitable manner. Number of tools secure such transparency, including:

· Publicly available environmental data.

· Peer reviewed environmental performance reviews of government policies.

· Corporate environmental disclosure.

· Reliable labelling for consumers, including eco-labels. And

· Environmental Impact Assessment of projects.

To conclude with a few key-words that we can discuss. Sustainability:

· requires independent and peer-reviewed science,

· it has to be economically efficient and beneficial,

· it has to be socially equitable and just,

· it must involve ownership and direct participation of all stakeholders (citizens, businesses and interest groups), and

· it must be transparent to ensure trust.

(Enditem)