Henry Huiyao Wang quoted in SCMP for advocating for rural land reform

The CCG President said equalizing property rights of rural and urban residents of rural households will immediately add vigor to the slowing economy.

Lately, you might have seen the recent advocacy for rural land reform by Henry Huiyao Wang, Founder & President of the Center for China & Globalization (CCG).

Today, the South China Morning Post (SCMP) dedicated a whole page to the debate. Below is its full report, where Henry was quoted in favor of further reforms.

China’s rural land is vast, vacant – and not for sale. Would putting it on the market spell windfall or woe?

China’s rural land, unlike urban property, remains closed to sales by individuals, foreclosing a potential source of economic activity

Debate rages over whether to open that land up to the market, with arguments against saying it would remove farmers’ main source of stability

Mandy Zuo in Shanghai

Published: 6:00 am, 12 Mar, 2024

Under an unassuming WeChat profile, “Baishun Farmer’s Property”, Zhang Ming provides updates on a large and growing market. Through this account, he shares details of new village houses in suburban Shanghai that are up for sale – a real estate listings board, unexceptional in most of the world.

Not so in China. Personal transactions of rural homes are strictly forbidden under the rules of property ownership. But at any given time, Zhang has information on over 400 houses scattered across the outskirts of the metropolis.

“Most of the owners have moved downtown and have no plans to go back, so they need to cash out,” said the property agent.

This grey market has persisted for decades, as a protracted debate has raged over whether urban residents should be allowed to buy rural property. It has remained a point of contention because of the potential consequences – a loss of agricultural resources for one of the world’s most populous countries and a burning of bridges for the roughly 300 million migrant workers who uproot their lives in the countryside to seek employment in population centres.

But researchers and former officials continue to advocate for the legalisation of such transactions, an action which would herald a new era for rural land reform for the country and have profound implications for its future.

China has gone through three rounds of land reform since the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949. The most recent, in 1978, allowed collectively owned land to be contracted by individual households.

Changing the rules on land in the countryside carries particular appeal at this moment due to several urgent economic issues. An ongoing property market crisis, an urban-rural divide which has blunted plans for revitalisation and a lack of suitable options to ensure sustainable growth in the world’s second-largest economy – all are problems which could be tackled, in whole or in part, via the opening of rural land ledgers.

The country recorded gross domestic product growth of 5.2 per cent last year – and has set this year’s target for “around 5 per cent” – but its post-pandemic recovery has been shaky.

“If rural land is made tradeable, I believe it can push the Chinese economy back to an annual growth rate of more than 8 per cent for over two decades,” said Meng Xiaosu, a retired official who spearheaded China’s property reform policies in the 1990s, at a forum in Jilin province last month.

He said that China’s future lies in equalising land systems in rural and urban areas and making rural residents rich via their holdings.

China has two different legal regimes for urban and rural land. All land in urban areas is directly owned by the state and can be leased to businesses and individuals on a contract of 40, 50 or 70 years depending on its use allocation. These automatically renew, thereby granting functional rights similar to private property ownership.

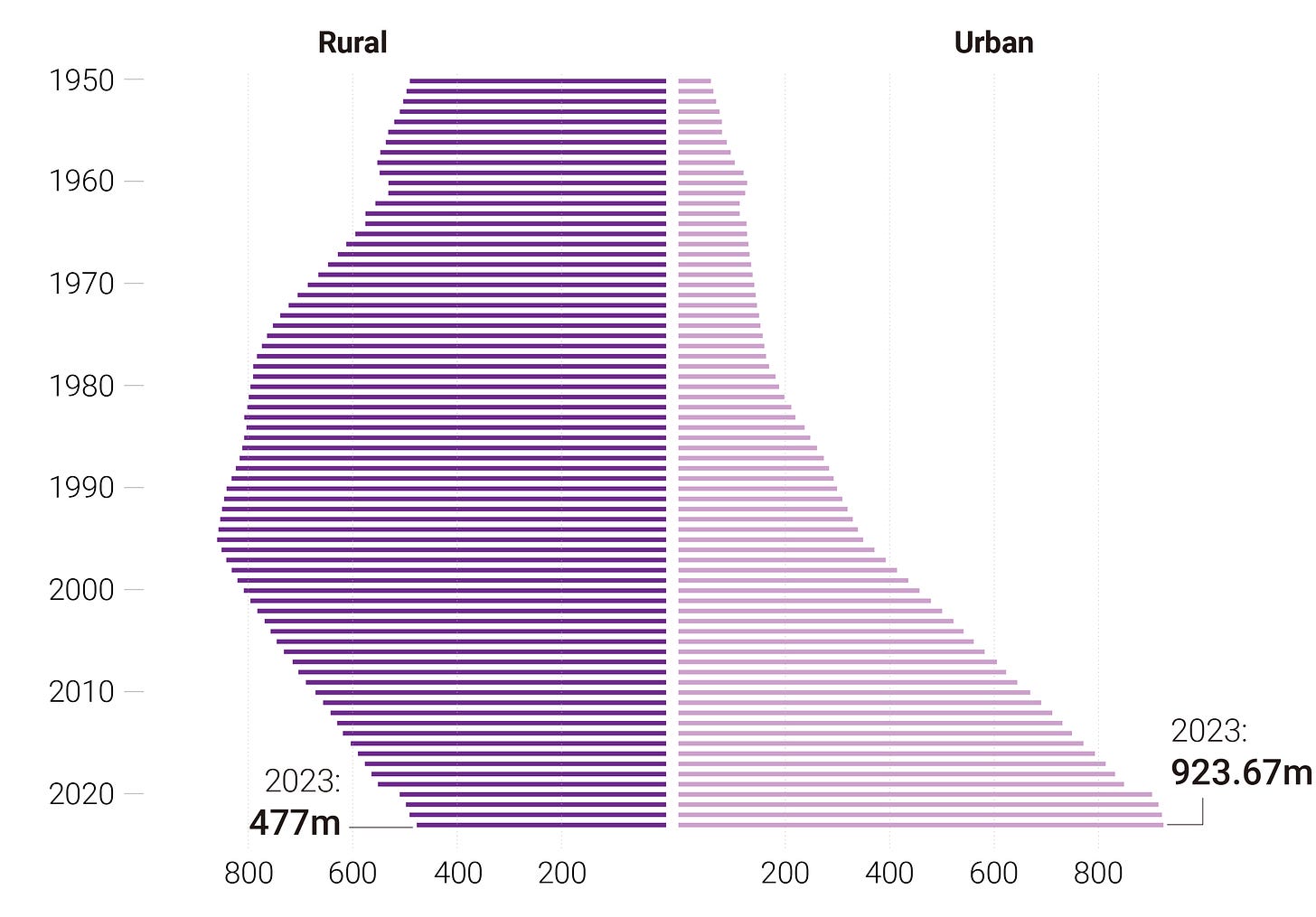

Rural land, however, is owned by village collectives, and can only be traded among members of the same village. This effectively keeps farmers from selling and buying their land or using it as collateral for loans, limiting their opportunity to raise capital and leading many to move to the cities for work. This has created vast swathes of abandoned land and property in the countryside.

The Chinese government has vowed to reform the rural land system – an object of frequent criticism over its perceived responsibility for income and social welfare gaps between town and country – but progress has remained sluggish.

At a meeting of top officials on improving the land management system last month, President Xi Jinping pledged to allocate more land resources to areas that are more economically developed.

“As for reformative measures that are exploratory but pressing, we should study them thoroughly and promote them prudently,” he said.

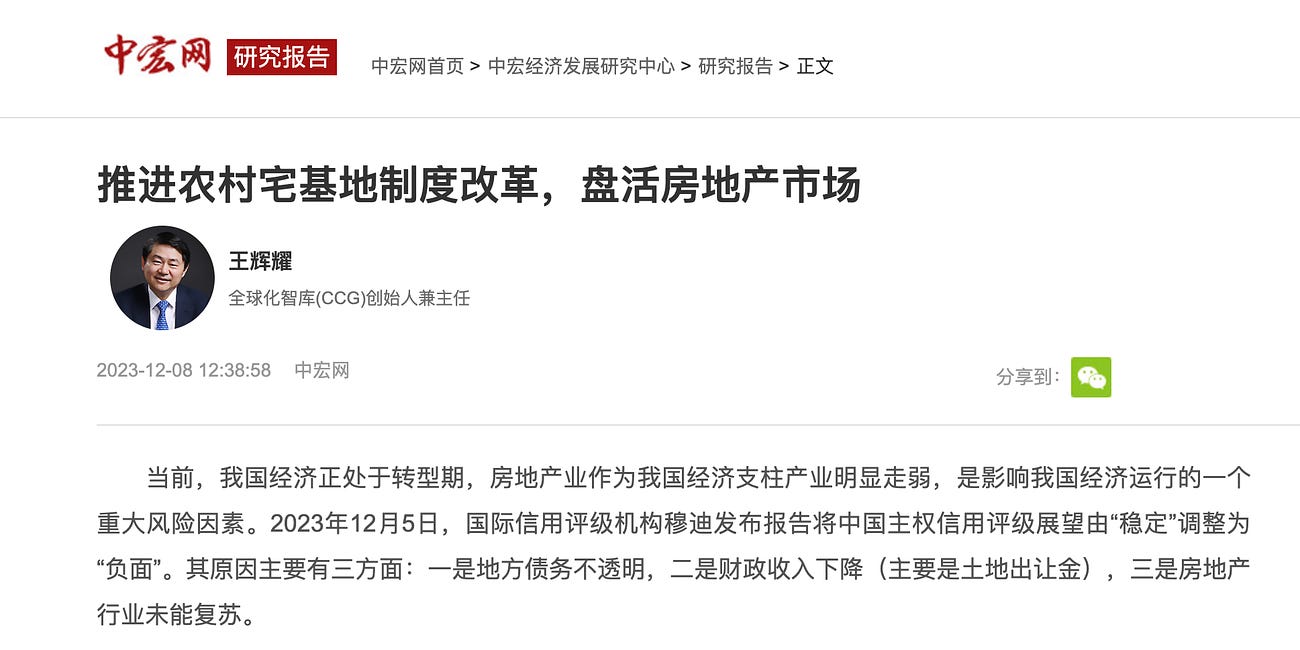

Wang Huiyao, founder of the Centre for China and Globalisation, a Beijing-based think tank, said that this is a signal for the acceleration of rural land reform.

“Economic growth was quite fast in the past and people might have not realised its importance, but now we’re slowing down,” he said.

“How to make use of the property left behind by China’s 300 million migrant workers to stimulate the Chinese economy has become an issue,” he added, citing a figure from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS).

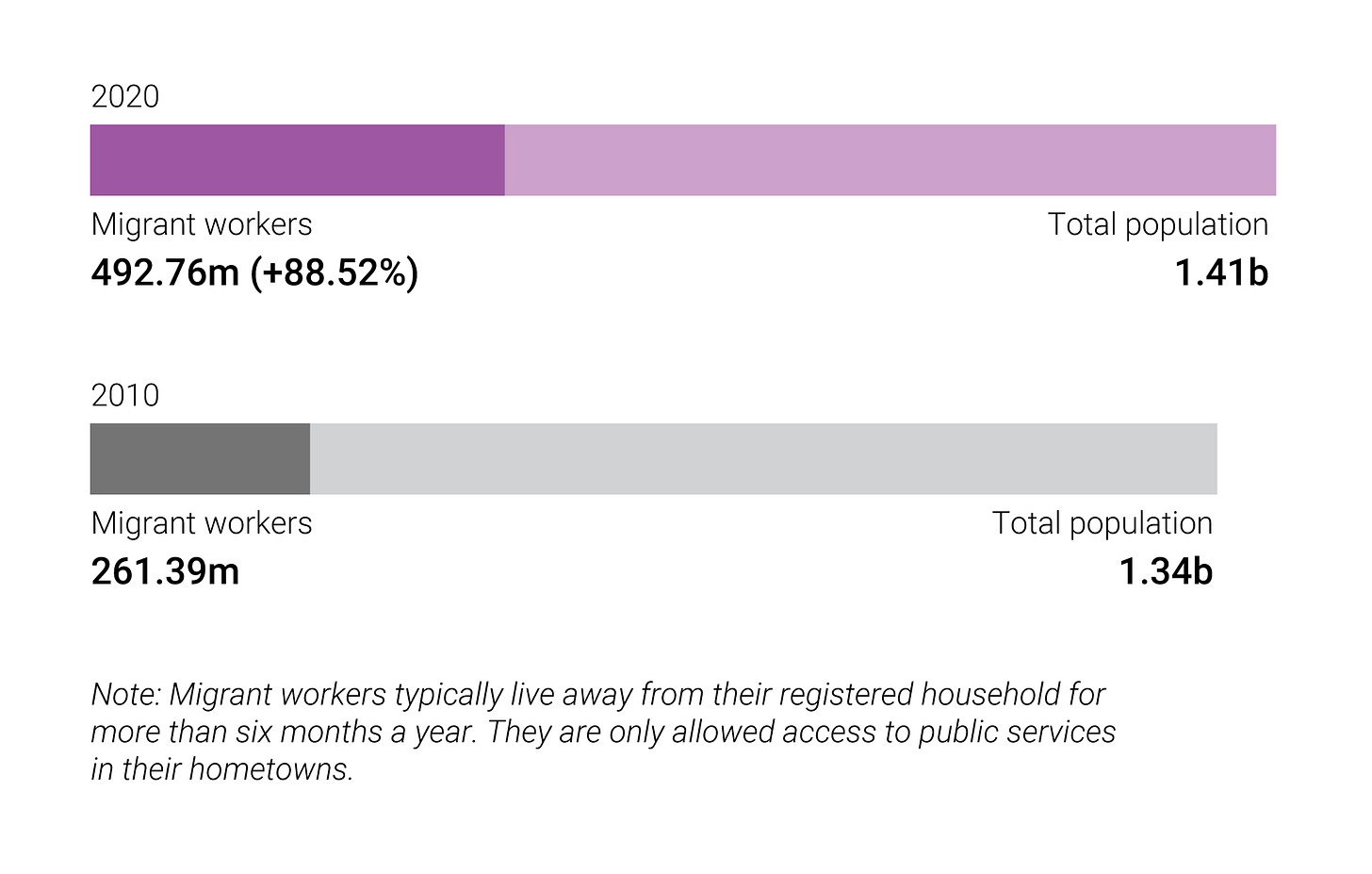

Migrant workers

Diving China’s economic boom

Those workers seek better-paid jobs in the city most of the year, but few have access to city residents’ superior social benefits as welfare systems are tied to the hukou, the national system of household registration.

They also miss out on capital gains from the real estate market due to lack of complete home ownership.

Despite some improvement over recent decades, the annual disposable income of urban households was still 2.4 times that of rural families last year, according to data from the NBS.

Wang said allowing free trade of rural homes will bring many urban residents to the countryside, a behaviour encouraged by the government in its campaign for rural revitalisation. That initiative was introduced in Xi’s report to the Communist Party’s 19th national congress in 2017.

“This will immediately add vigour to the economy and support high-speed growth in China for another 20 years,” Wang said.

Other academicians and officials have made similar appeals in recent months. Outspoken former finance minister Lou Jiwei projected that China’s overall consumption demand could increase by nearly 30 per cent if the “rural-urban dual structure” is broken.

When China stops dividing the population based on where their hukou is registered, and migrant workers are given the right to sell their village houses, then they will “feel assured to buy property in urban areas” and unleash great purchasing potential, he said at a forum in Shenzhen in December.

But many worry such reforms will do more harm than good.

“Homesteads are the last resource for farmers. They will at least have a place to return to if one day they encounter trouble,” said Jin Chong, a village cadre in suburban Shanghai, referring to land allotted to farmers by the government to build homes.

As party secretary of Yuli village in Fengxian district – one of over 100 county-level localities designated by the central government as sites for land reform – Jin said the district is not experimenting with allowing urban dwellers to purchase rural homes.

“Reform in this regard has been laid aside. There’s no word from above and we’re not exploring this direction,” he said.

Like Fengxian, most designated counties are making mild changes such as moving villagers to towns and leasing their homesteads to businesses through the village collective for commercial development.

He Xuefeng, dean of Wuhan University’s School of Sociology, said keeping things the way they are means social stability in China’s vast rural expanse.

“The situation today, as President Xi put it, could be one of ‘terrifying waves and stormy seas’,” He said. “So where should farmers go when this occurs?”

Xi has used the phrase repeatedly as a metaphor for the complicated and dangerous environment China faces, with domestic as well as geopolitical challenges.

He Xuefeng raised Taiwan as an example. In 2000, rural land was made tradeable there, only to be followed by an unexpected frenzy of luxury villa construction in the name of agricultural development.

“How can farmers fight the force of capital? … As a disadvantaged group, they will lose their basic source of security if free trade of rural land is allowed,” he said.

A survey of over 115,000 people from across China, conducted with the aid of Wuhan University’s rural governance research centre during last month’s Lunar New Year holiday, shows how split farmers are over the issue.

Nearly 46 per cent of the surveyed said they wanted rights to farmland to be adjusted based on change in population – meaning those who have relocated to cities should give up their rights and be compensated – while the rest said they wanted things to remain unchanged.

This means “there’s no public consensus yet” and policies should be steady, the researchers concluded.