Founder and Director General of the Paris Peace Forum speaks at CCG

Full speech of Dr. Justin Vaïsse, where he calls for the U.S. and China to regulate and moderate their rivalry.

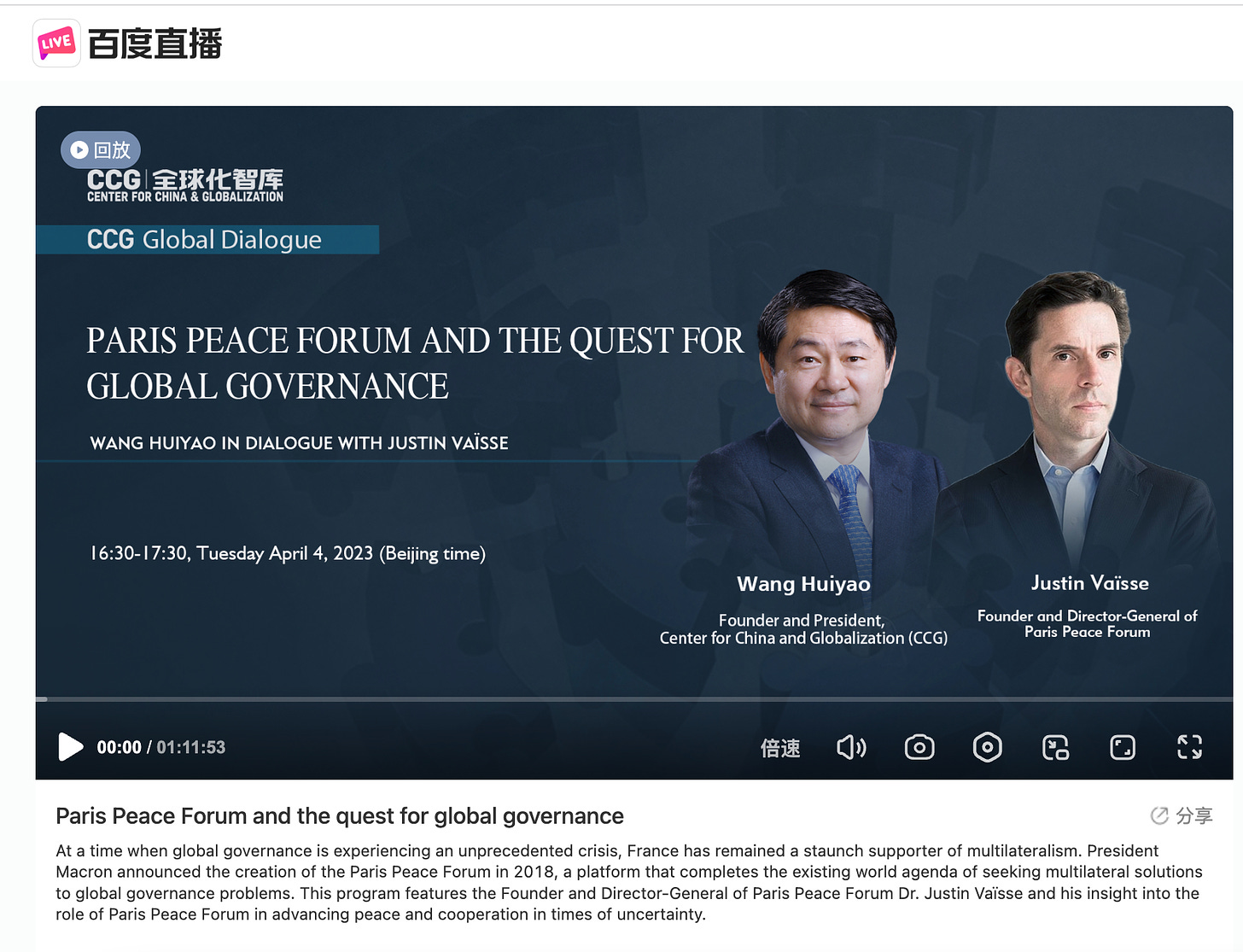

On the eve of French President Emmanuel Macron and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen’s visit to China on April 5 to 7, Dr. Justin Vaïsse, Founder and Director General of the Paris Peace Forum, spoke at the Center for China and Globalization (CCG) and had a dialogue with Henry Huiyao Wang, Founder and President of CCG, on Tuesday, April 4, 2023.

Dr. Justin Vaïsse was the head of Policy Planning at the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs from 2013-2019. Justin Vaïsse also served as Director of Research at the Brookings Institution in Washington (2007-2013), with a focus on transatlantic relations and European foreign policy. A historian specialized in international relations and American foreign policy, Dr. Vaïsse has written and co-authored numerous books translated in multiple languages, and has held teaching positions at the Paris School of International Affairs of Sciences Po, and the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University.

CCG Secretary-General Mable Miao Lu opened the event by introducing the keynote speaker, emphasizing that over the past five years, CCG has been only official Chinese partner of the Paris Peace Forum and has attended multiple sessions of the conference. CCG looks forward to further cooperation with the Paris Peace Forum and Dr. Vaïsse in the future.

The event was livestreamed domestically in China.

Here is the replay on YouTube

The following is the speech as transcribed by CCG staff. It hasn’t been reviewed by Dr. Vaïsse. (CCG wills share the transcript of his dialogue with Henry Huiyao Wang later.)

Thank you, Mabel. Thank you, Henry. You've been really at the forefront of exchanges with the rest of the world in the past few years, including during COVID, then right after COVID, and that includes cooperation with the Paris Peace Forum from the start in 2018, for which I'm really grateful for.

So, as you know, I'm not an official, and nothing I say can be attributed to the French government or to the EU Commission. Actually, we have a partnership with the French government and with the EU Commission among others. But the Forum is an independent organization, and half of the governing organizations that make up the the forum come from the global South. This is why I will say a few words as a European, but also from a global perspective, as a globalist, and from the vantage point of the Paris Space Forum, which has been building bridges between North and South, but also between East and West, since 2018 to try and address some of the world’s most difficult challenges in an innovative way.

Each year, we've been lucky to have a Chinese delegation, not only one from the Center for China and Globalization, but also a governmental one. Each year, several ministers from Beijing. In 2019, Vice President Wang Qishan gave an opening speech. And in 2020, the year of COVID, when we held the edition online, President Xi Jinping intervened through video.

Today, I would like to say a few words on the future of global governance in a polarized world. We know two things about the current age of the international system. One that great power competition is in full swing, especially the US-China rivalry, making competition an inescapable feature of our world. Second, we know that global challenges like climate change and pandemics and others, will grow ever more existential for human beings, making cooperation necessary. In the past, if you want a metaphor, passengers of the ship called Planet Earth could quarrel as much as they wanted. They could fight among themselves. The ship would keep sailing. But with climate change, disappearing biodiversity, dangerous pandemics and the perils of technology, passengers just can't ignore the icebergs and the storms coming, and they need to face them together one way or the other. So the question is, how do we combine? How do we articulate competition with cooperation? The inevitable, with the necessary?

Let me jump to conclusions. I believe the US and China have a responsibility to regulate and moderate the rivalry in the face of global dangers like climate change, and I believe Europe as a responsibility to push in that direction and lead in offering initiatives and solutions for the global public good. Lastly, I believe that other actors than states can help smooth the competition and help solve global problems. So I will offer five remarks in this to that effect. First remark, the demand for global rules is growing faster than our capacity to produce these rules, and that comes for several reasons. One, because of growing multipolarity. The US as the dominant power between the 1990s and the 2010s, more or less, used to provide many of the public goods the rest of the world relies on.

Let me give you a very, very concrete example, which is one of the areas in which the Paris Peace Forum is active, which is space and the sustainability of orbits. So what happens when a satellite from China, or from Egypt, or from France, or from the US is on a collision course with another one? And as you know, there are more and more satellites and more and more debris, especially in the lower orbit, so there's danger and there's no space traffic. So it's not like in the street, or even like in the air. No one regulates that. So it's a common space, a global common that all humans are using, or at least the spacefaring nations. But that is not regulated. And so what happens when there's a danger of collision is that the 18th Squadron in the US of Norad sends a collision data message to the owner of the satellite that is in danger, in order for that, owner of the satellite to either move the satellite or delay it, or take any other evasion measure. That can be confirmed by national means for China or for the EU, for example, has means to be aware of collisions. But, but basically that service is still pretty much provided by the US. So that example means that because we have an increasing situation of multiplarity, not unipolarity, the US will not keep providing that for the rest of the world for much longer. Because it was its interests before, when it was very dominant and when there were not so many objects in space. But right now, because many other nations have grown, starting with China, probably it won't do that. So that’s one of the reasons why we need more rules.

We need to decide how we administer space traffic, and how we make sure that we can enjoy the benefits of space through satellites without having collisions threatening that. And Second reason of our big need for rules is technology. Because technologies are then seeing fast and faster than any other moment in history. It opens up many questions. And as usual, man creates technology, and then we have to regulate it. But regulation only comes afterwards. And so we'll have to agree on a number of things in the digital space, in the space domain, also in biotechnologies, and in number of other domains where we'll need more rules. Third reason is because of the degradation of the planet, as we all know, where the situation is for climate change, and the very clear risk of overshooting 1.5, which is pretty much certainty at this point, and also the disappearance of biodiversity, which is threatening in many other ways.

So here again, we need rules. But of course, the difficulty is agreeing on these rules. I remember about ten years ago when the EU tried to put in place a system of taxation of emissions for aviation, for planes. You may know that among the different industries or domains that emit CO2, aviation and the [inaudible] industry, ship transportation, are not taxed, which is very shocking, because obviously, generally people taking planes have the means to pay taxes on the CO2. They emit, but they're not taxed, because that comes from a longstanding arrangement among nations. So about ten years back, you tried to put in place a plan to tax emissions coming from flights, but it was rebuffed by the US, China and India in particular, that threatened to stop buying [inaudible] planes, and so the EU folded its plans, and aviation is still not taxed in any way, which indeed is a problem. So that was just one example illustrating the fact that we need common rules if we are to address these challenges.

And the last reason, I think, is that people demand it. That is to say, people are very much aware of these global challenges, and they're asking for rules. You know, most of the time, national governments cannot provide these rules, because these are global problems that ignore borders. And so you need some kind of international coordination to put in play those rules and there's a sort of a gap that people can't just address themselves to their government, but they need to be some kind of cooperation. So first remark, we need more and more rules to manage that international system, but we have limited capacity to do so.

Second remark: competition, including US-China competition can be good sometimes for the world, if it's kept in check. So when you think about competition, it's not altogether bad, right? So if you think of the Cold War, for example, the Cold War prompted the US and Russia and China and Europeans and others to compete, for example on space issues, or on technological process, on the digital domain, etc. The Cold War was pretty much one of the motives behind the technological advances that we've known. I mean, the race to the moon is a good example of that, and it produced good things for the world. So competition can be good. Let me give you a more recent example. Solar panels. You may be familiar with the story of solar panels, especially for us Europeans, where we were overtaken by Chinese production of solar panels, etc. But at the end of the day, the large, massive production of cheap solar panels is good for the world, right? So because what we need is to decrease the emissions of CO2 that we have by, I would say, by which of a means, obviously I would have preferred Europe to be able to produce more of them, especially its own. That's not how it happened. But Europe now is trying to to compete. And so I think in this example, again, competition is good.

A third example is on infrastructure in the developing world, and debt. So here, again, it's good if it's additional, not just a zero sum game. But obviously, there's limits to that. So one of the big challenges of today is making sure that we have an international financial architecture that allows developing countries to access liquidity to finance their quest for this, for the SDGS, and also to ensure that they can make their green transition. Development for them more generally comes before the green transition. But the two are are linked, and interestingly, was in 2015 that the world gave itself two sets of rules, or two agendas, I would say, three months apart. One was in September 2015, with the SDGS at the UN, and the second set of rules was with the Paris agreement in December for the climate goals, including the 1.5 Degree Goal. And so the question now is how we reconcile them, and how we make it so that China, the US, Europe and others can cooperate in providing sufficient financial resource for these countries, not only for their development and getting out of poverty, etc, but also for their climate transition.

Interestingly, President Macron has convened a summit on June 22 and 23, called Submit for a New Global Financial Pact that will be, I think, very much attended, and where China is expected among others. And the reason is, China has been going outside of its borders quite a bit in the past three years, has been building infrastructure, has been lending money to many of these countries. And so China needs to be part of that solution, or that reform of international financial flows to make sure that these countries have either resolution of the debt when when they are in distress, when they are in a crisis. And on the sort of longer term, they are able to finance themselves and finance their their transition. And so there are many things that should be done, but the issue of debt is one where China is now a big player. And here again, the sort of virtuous circle of competition needs to prevail, not the vicious circle.

Here one last example of of how competition can be can be good. Critical minerals. We all know that in order to succeed in the green transition, but also the digital transition, we will need massively more critical minerals, lithium, cobalt, coltan and many others, rare earth that we produce now. And so, as humans, we all have an interest in making sure that these are produced massively, so we have enough of them, and that they are produced in acceptable conditions that don't replace one environmental problem with another one. And also in terms of norms, in terms of social norms etc., that they are mined, and that they are harvested in good conditions.

So competition can be good and China has acquired a sort of a dominant position in this domain, it has been stimulating others to do the same thing. But of course, the question is whether it is one of virtuous circle or a vicious circle. If that competition pushes us to adopt higher standards, in terms of making sure that, for example, when we have mines in Africa, in South Asia or in Latin America, we have standards to do transformation in these countries, and they are able to get the fair share of the minerals which are extracted from their own territories. It would be good. Of course, the vicious circle version of that would not be desirable, which is that the US, china, Europe and others compete in a race to the bottom with corruption, and lower environmental and social standards. So the Paris Peace Forum, and I will mention that briefly in the conclusion, is starting an initiative to try to have common standards among great powers including China, on this issue.

The third remark are more often, unfortunately, competition is harmful and dangerous, that's why it needs to be moderated. It needs to be regulated, especially for the US-China rivalry, even though COVID through into relief the mutual vulnerability of all nations, even rival nations, and the need for positive cooperation. Great power politics often prevail, and are taking on zero-sum logic. The risk is that all issues would become zero-sum, and we would only have issues when we compete, including the issues where we have a common interest in cooperating. So basically, either you tame the competition, reduce it, try to keep it in checks and try to regulate it, or you decide to compete widely and compartmentalize. So you say, we'll be rivals in the geopolitical sphere, but we will cooperate on climate, etc. But of course, the danger is that compartmentalization is difficult, and sometimes it's not working. For example, a month ago, john Kerry, the US special presidential envoy for climate, was telling a journalist that his discussions with his Chinese counterpart had stalled because of the larger tensions between the US and China. Because of the balloon, and all the different irritants between the US and China, the joint efforts they was making with Chinese counterpart had diminished. So I'm not sure we really have the option to say that we can compete freely. But then we'll compartmentalize, and we'll keep cooperating on other issues. I'm worried that the field of cooperation will be contaminated by this competition. It's even worse because subjects of cooperation can sometimes be taken hostage. We all know the recent tendencies that interdependence among great powers are weaponized, either through trade sanctions, or through migration flows, or through digital domain. So even where it's conceivable that we could cooperate, sometimes it's used as a tool of competition. So sort of addressing my theory that compartmentalization probably will be very difficult, and so the only solution, in a sense, is really to reduce competition.

I'm taking inspiration for these remarks from the dinner that CCG organized at the Munich Security Conference a month and a half ago, where Mabel and Henry were present. They invited me to have a discussion on climate, and Graham Allison was making the point that it's even conceivable that this could extend to a sort of MAD theory from the Cold War, which is mutually assured destruction theory in the nuclear domain, one of the parties taking a global issue hostage in order to compete. And even if we leave the global problems like climate change aside, even extreme tension between the US and China in particular, whether it remains conventional or geopolitical or it becomes a nuclear, it is just bad news for the rest of the world, because polarization will increase, it will have an impact on trade and the rest of political relations, etc. So I don't think there are other ways to manage that competition in order to leave some space for cooperation.

Fourth point is that the situation calls for more leadership on both sides (US and China), but also on Europe's side, to propose a third way, and not let that sort of face to face situation prevail, instead have some kind of a triangular relationship. Paradoxically, I think it will be more stable if it's triangular, rather than just face to face. And it's interesting to notice that during the Cold War, even at the time of great tension between the US and the USSR, the superpowers managed to cooperate. It's true that it was more in the 1990s and 1970s than at the beginning of the Cold War, but they managed to cooperate and even signed UN binding treaties, whether on antarctic, space, arms control, or cooperating smallpox eradication, which was one of the big victories in global health during the Cold War. And it's striking that it seems now is more difficult to get anything through the UN than it was during the Cold War, at least during the 2nd part of the Cold War. So not everything is going in the wrong direction. A couple of months ago, at the end of 2022, we had the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Agreement, I think that was really important, and China played a positive role. I think that's something to be appreciated. And the 2nd thing was even more recently, last month, the agreement on the treaty for the high Seas. We don't have the treaty yet, but there was a decisive agreement leading later this year to a treaty which is called BBNJ. It's basically about protecting the high seas, and everything that is beyond national jurisdiction in the high seas. And it's really important, because protecting biodiversity in this huge swath of planet Earth is really important. So, you see, there are some good signs, and I think we can cooperate in the multilateral domain.

But, if we take a step back and look more generally, things are not great for the rest. So all of these calls for diplomacy, obviously between the US and China, but also with others. And I think the EU has a lot to offer in that. President of the EU Commission was Ursula von der Leyen, called it diplomatic de-risking rather than decoupling. And I think that's a much more promising root than decoupling, which will necessarily harden lines between the powers. And 2nd, that calls for a reinforcement of the UN and playing the full game of multilateralism, that is to say, binding rules, and cooperating on these binding rules. But I think that's not enough.

That leads me to my final point, my 5th point, which is about the Paris Peace Forum, because that's the title of my talk and that's what we're doing. I think that all the forums of cooperation are necessary. There is to say, the US and China should learn more to mix cooperation and competition, which are inescapable and indispensable. And I think that Europe can help in this regard. I also think that civil society and other actors in international community can help as well. In many domains, intergovernmental cooperation is largely blocked or it's not sufficient to address global challenges. And in any case, if you think of it, the world is both more polar and less polar. We've been talking about bipolarity in the Cold War, then uni-polarity, then now multi-polarity. But the question is what is polar? The polar is a sort of concentration of power in the end of a government, or a number of government? Governments have been taking on more importance during COVID because of rising tensions.

All of this reinforces the traditional nation state. That's the whole story of Europe in the 15th, 16th and 20th century. And the competition among European powers during that period obviously led to European advances in weaponry, technology, economy, etc. So you see competition with both good and bad. But my point is that we see more importance for governments now that we have more polarization, but also less. And if you look at many domains, you'll see that there are other forces. So let's take technology in general. We see that in the 20th century, technology would be often coming from the state. Nuclear technology for example, was largely developed by governments and was harnessed by governmental institutions, labs, research apparatus, etc. But if you think of the digital domain, that has increased considerably in the last 30 to 40 years, is largely in the hands of the private industry. And so it's not exactly the same thing, and same you could say for bio-technology and other aspects of technology that are largely in private hands. Or if you think of many other domains, like global health, you see many other actors than governments, philanthropic foundations, NGOs and others. And so there is an array of issues which is more effective, there are no other way than making progress in a different setting, associating other actors instead of just governments. And that's what the Paris Peace Forum has been doing for a number of years.

So we do have governmental representatives, we associate forces from the private sector, from civil society, think tanks and others, and we build these coalitions around issues that are currently blocked at the UN. So we try to help that process, try to make progress in norms and political mobilization. I mentioned space. We launched this initiative called Net Zero Space with a number of companies around the world, but also space agencies from North and South, including Chinese companies in that consortium, in that coalition of action, trying to stabilize and then diminish the amount of debris in the North orbit. So we make orbit sustainable, and then we can enjoy space for decades and centuries to come. We don't spoil it like we have spoiled many parts of the Earth. So that's the Net Zero Space Initiative. I should also mention good cooperation with China in what we launched a year ago, which is called Climate Overshoot Commission, it is headed by Pascal Lamy, the former president of the Paris Peace Forum, which will give its conclusions a bit later this year. So Climate Overshoot Commission looks at what we do when we go beyond 1.5 degrees? Unfortunately, as I mentioned, it's most likely that we will go beyond 1.5 degrees. Reduction of emissions is key. It's should remain central. But we have to think a bit further and think about what we do more in terms of adaptation, because we'll suffer through the consequences of climate change, even if we are very good on mitigation. Since it's cumulative, there will be more global warming, so there will be more bad consequences for humans. And also, how do we do with these technologies that could provide part of the solution? How do we put in place some global governance of the system? And I'm thinking of carbon capture and solar engineering. These are pretty controversial technologies, but that need to be discussed among all nations and among all actors. So that's what the Climate Overshoot Commission is, and it is made up of 15 commissioners, including a Chinese commissioner.

One last example I quickly mentioned it earlier, is Critical Minerals, where the forum has launched a co-action pretty much along the lines that I was describing earlier. That is to say, we know we need these minerals in great quantities to unsure the green transition and the digital transition, but we need to make sure that competition here again, doesn't block or hinder this production, and that we do it in conditions that are socially, environmentally and geopoliticallly acceptable to all. And so that's one of the reasons why I came to China on the occasion of President Macron and President von der Leyen visit China, to make sure that we can have Chinese participation in this initiative, in in particular, given china's role there. So I'll stop here. Sorry, I have been a bit too long, but I hope we can start from there to discuss. Thank you.