Chinese Returnees Studies by David Zweig

Data-packed research by the Professor Emeritus at HKUST on the contribution of Chinese students educated abroad to the development of China

Hi, this is Yuxuan Jia in Beijing. On Dec. 28, 2023, a seminar titled "Chinese Returnees Studies and International People-to-People Exchanges" was co-hosted by the Center for China & Globalization (CCG) and the Alliance of Global Talent Organizations (AGTO). AGTO is a non-governmental organization proposed by the CCG and launched at the third edition of the Paris Peace Forum on November 13, 2020.

The seminar focused on the contributions of Chinese students educated abroad to the development of China and the country's communication with the world, especially in light of President Xi Jinping's announcement in San Francisco that "China is ready to invite 50,000 young Americans to China on exchange and study programs in the next five years."

The event featured speeches by David Zweig, Professor Emeritus at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST), CCG Vice President, and AGTO's director of research; Henry Huiyao Wang, CCG President and AGTO's Director-General; and Mabel Lu Miao, CCG Secretary-General and AGTO's Deputy Director, followed by a panel discussion of the three.

The event was covered by China News Service, www.china.com.cn under the auspices of the State Council Information Office, and China Scholars Abroad under the auspices of the Ministry of Education. The full video of the event is available on CCG's official WeChat account and YouTube.

Prof. Zweig's speech was delivered in both Chinese and English. This newsletter provides a complete English translation.

Thank you, it is a pleasure. For me, this is a rare opportunity to share on this platform with my old friends. It was only at 11 o'clock last night that I found out Henry wanted me to speak in Chinese; originally, I planned to speak in English, so I will do my best in Chinese, and you can read the English PowerPoint. There might be some words I don't know, but I will try my best. If there's anything you're unsure about, you can go check my profile.

So, the first question is, why do I study overseas returnees? The answer is that I was once a Canadian student studying abroad. [To quote Mao Zedong, with]"utter devotion to others without any thought of self", I came to China from thousands of miles away. I participated in many specific activities. Back then, it was "开门办学 running the school in an open way" [an educational initiative during the Cultural Revolution that required all students to educate themselves in factories and rural areas], and we worked in factories. I still remember that time my beard scared some Chinese children and made them cry; that was in 1975. And this is the Class of 1976 of Peking University. This photo is very valuable because it includes some consul generals and ambassadors, and I can introduce them when there's a chance. This is me, so I inserted this photo.

But why am I interested in overseas returnees? Firstly, I am interested in transnational relations. I think this is a concept of comparative politics. A thing, a service, whatever it is, when it crosses the border from one country to another, its value is likely to change. This means that my human capital may be elevated after I go abroad and that I might be more valuable when I return to China. That's why I am very interested in this subject — not just about Chinese students who study overseas but also in terms of technology.

I used to study joint ventures in east China's Jiangsu Province, where a brigade [a grassroots level of administration equivalent to a village during the people's commune era from 1958 to 1983] secretary told me that if he could bring some new technology from Taiwan to the Chinese mainland, he could make a lot of money because these technologies were not available in the mainland market. So, for that reason, and more importantly, because the things returnees bring back from abroad are of great benefit to China, and therefore to themselves, I began to study Chinese returnees.

In today's session, Henry Huiyao Wang mentioned the study of overseas returnees. I have a theory called "Shortage Theory", and maybe next year, I will publish a book to further discuss this topic. Basically, the theory can be explained in this way: as an overseas returnee, the most important thing is to find what China needs and lacks. If you can put this into practice back in China, you will be successful.

I discovered this during my visit to the Changchun Institute of Applied Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) in 2003. Some researchers there said that when they went abroad they specifically tried to find a "缺门 or gap", which means things that China lacks. If they brought these things back, the CAS would grant them a laboratory. Scientists competing for jobs at CAS, and specifically for the 百人计划 Hundred Talents Program, had to present their research and convince a committee that what they had was new for China.

In the first decade of the 21st century, this was relatively easy because China then lacked many technologies. To put it in English, the "scientific landscape" was vast. Therefore, one could study abroad, not necessarily the most advanced things, but the relatively advanced things that China might not have. And bringing back these technologies would greatly elevate their position in China. Only now this has become more difficult.

The Chinese government and leaders also recognized this "gap", and they have been highlighting the importance of addressing this shortage for a long time. This concept has been mentioned in many documents since 1996 which saw the release of the Ninth five-year plan (1996-2000), or maybe even earlier. For instance, an article, "深圳需要什么样的人才?"(What kind of talent does Shenzhen need?) listed the talents in short supply in Shenzhen — finance, IT, foreign trade, tourism, biotech, and computers. The Shanghai government also mentioned the need to attract "persons who have patents and inventions or technology leading in the world or filling gaps in the projects urgently needed at home. . . . And personnel who have obtained a Ph.D. degree in urgently needed professional fields." In May 2002, the "2002-2005 Outline for Building the Ranks of Nationwide Talent" put the emphasis "on importing high-quality talent which is in short supply." The Chinese government has always been placing great importance on this aspect.

My theory has two other components: the second is environment, including the macro environment and the company's environment.

I believe Chinese scientists, scholars, and businesspeople will return if the macro- and micro-environment allow them to benefit from their "shortage goods" or their advanced human capital. However, for instance, sometimes in a company, jealous people would say, "Oh, that's a foreigner who came back from abroad, I don't want to lend my help", so the returnees might feel constrained and dissatisfied because what they brought back cannot realize its full potential, and that's a problem.

I am very interested in many organizations' 内部环境 internal environment because this is closely related to political science and organizational theory. What matters most is how to govern an organization. To attract the tide of reverse migration, the state must create a political, legal, economic, or social context attractive to home country nationals living overseas. The bias should be reduced or restricted.

Poo Mu-ming, a well-known returnee who previously worked at University of California, Berkeley, is now in Shanghai. He suggested very early on that "obstacles to Chinese research institutions achieving excellence are cultural rather than economic". A good culture is essential. "The most urgent task in building research institutions in China is the creation of an intellectual atmosphere that is conducive to creative work." Until then, "a significant flow of scientific talent is unlikely."

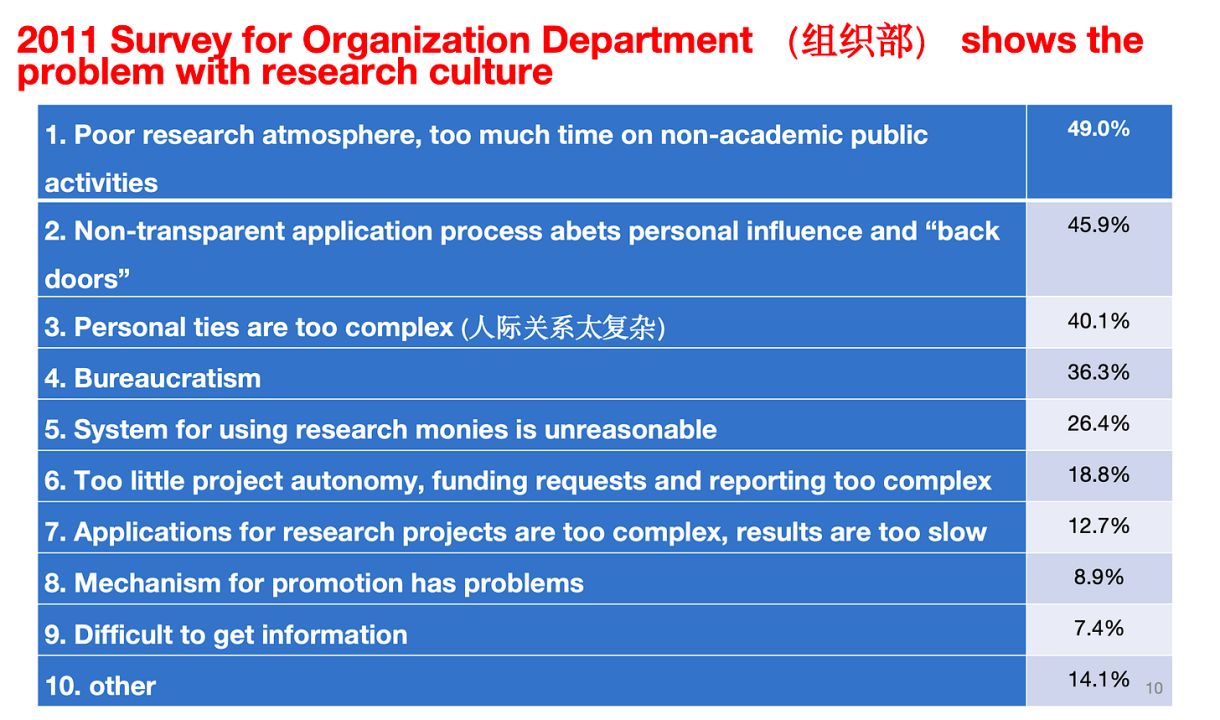

This is interesting. In 2011, the Organization Department of the Communist Party of China (CPC) conducted a social survey. They asked the returnees, "What problems are you currently encountering?" One of the most common issues identified was that personal ties are too complex, a widespread problem in China. This problem can also be found in foreign companies, but we should keep in mind that the Chinese culture is very thick, and interpersonal relationships in the Chinese culture are particularly important.

Another major concern is the poor research atmosphere. Many returnees reported that they had to spend too much time on non-academic public activities. Although some of the returnees wanted to come back to become officials, many of them just wanted to focus on their research, and they didn't want to be involved in too many things other than that. Another prominent problem is bureaucratism. These problems should be thoroughly eradicated.

The third aspect of my theory is the rewards or remuneration. Before somebody comes back to their home country, the organization at home may promise certain kinds of benefits. However, if the organization fails to fulfill its commitments upon their return, it leads to the dissatisfaction of the returnee.

The foreign affairs office of Fudan University once promised a good friend of mine a house if he came back from Japan. However, it didn't fulfill this commitment, which upset my friend, even though he could afford to buy one later. So, if you want to motivate returnees, you should give them the value they deserve, and they should able to fulfill their role.

From 1991 to 2019, many friends and organizations supported and funded me in my research. Early on, I got excellent help from the Foreign Student Office at Nanjing University and from the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong. I also had excellent research assistants, some of whom were students at that time. They are now professors at Renmin University, Chinese University of Hong Kong (in Shenzhen), and Peking University. I also had two female students helping me, one of them is now finishing her PhD at Princeton University, and the other is pursuing her Ph.D. at New York University. With such assistance, I published papers collaborating with these students, and I always ensured their names were included in the paper, which I hoped would be helpful to their careers.

My first research was China's Brain Drain to the United States, a book written by my friend 陈昌贵 Chen Changgui [Professor at Sun Yat-sen University] and me. (We also got help from Professor Stan Rosen of the University of Southern California). We interviewed 272 Chinese people who stayed in 5 cities in the United States to understand whether they were willing to return and why. I gave them seven options ranging from "definitely return", "likely to return", all the way to "definitely will not return". This survey showed what kinds of attitudes they held, and what particular backgrounds and situations they were in.

I had several important findings, and one of them is: that the first 3 groups (definitely return, already had plans; definitely return, but can’t say when; likely to return, have kept strong contacts in China) composed 35% of the sample. So even though this survey was done four years after 1989, 35% would probably return if things in China remained calm and the economy developed.

Many voices were saying those Chinese people would never return, but we said no. Mao Zedong said, "No investigation, no right to speak." However, we had the right to speak. Why? Because we conducted our investigations.

What were the factors pulling them back then?

The first was the age of their children. Those with children in junior high or high school would not return because they wanted their children to attend universities abroad. But if the children were younger, it was possible to go back.

The second factor was the spouse's attitude. When we conducted this study in 1993, many women were unwilling to go back because they already owned a house in a small town in the United States. Returning to China meant having no house to live in. However, the situation is different now.

Third, due to the one-child policy, students who studied abroad were the only child in their families. Consequently, they would feel obligated to return if their parents were in poor health.

Also, 80% said they would return because China needed technology exchange. Chen Changgui published several books based on our research and also an important article in Qiushi.

The second research I conducted was "Parking on the Doorstep: Mainlanders in Hong Kong" conference paper, which focused on returnees who lived in Hong Kong and had not yet returned to the mainland. In the 1990s, many Chinese students who studied overseas moved to Hong Kong to work at universities, as lawyers, or in finance and investment. I knew them and conducted surveys. At that time, foreign law firms could only establish one office in China. So many people might have the intention to come back but had nowhere to go. Later, after China's opening up in this field, every city could have a law office, so people were more willing to return. Living in Hong Kong was a good choice at that time since the returnees' parents could visit their grandchildren easily.

At that time, there was a policy that people from the mainland could stay for up to three months in Hong Kong. Therefore, during the Spring Festival, the returnees' parents would frequently come over. In Hong Kong, their income could be guaranteed, and their housing was decent. They could also maintain contact with people from the mainland. There were many joint programs between the Chinese mainland and Hong Kong, including some cooperative projects between 自然科学基金 the National Natural Science Foundation of China and Hong Kong's Research Grants Council. All in all, staying in Hong Kong could offer returnees many opportunities to interact with the mainland.

I plan to publish a book next year, which will discuss the theory I mentioned before. The subtitle of the book might be "Towards a Theory of Shortage", focusing on the theme of scarcity, particularly in terms of talent.

First, I will talk about academics. The funding of Project-985 proposed in 1998 contained one criterion, that out of the massive funding it provided to a bunch of universities, 20% of these funds should be used to attract overseas returnees. Another criterion used to evaluate the quality of universities at that time was the number of articles a university had published in foreign periodicals, and those who could publish internationally were overseas returnees. Thus, this policy turned overseas returnees into a shortage good, or a "gap", something China urgently needed, making returnees very valuable to the university.

Li and Pu published an article after interviewing twenty university presidents. These university presidents believed returnees had a global vision, better training, and high-end technological expertise needed to build world-class universities, referring to them as "rare goods." This also supported my "gap" theory.

Some universities considered it a very important task to transform the micro-environment on the campus.

The first example is Justin Yifu Lin. After he returned, he established the China Center for Economic Research [now the National School of Development at Peking University], where all staff were overseas returnees with high salaries and flexible working hours. It can be said that he created a small environment and influenced the other universities to attract more foreigners.

I also did some research in the Shanghai University of Finance and Economics and Southwestern University of Finance and Economics. They had several interesting reforms, one of which was the introduction of "part-time deans." Why is this important? Because if a part-time dean wants to make significant reforms within the school, they wouldn't have to worry about conservative forces subverting their power. But they would have less fear, as they also had a good job in the United States that they could return to. 边燕杰 Bian Yanjie, for instance, is a part-time dean at Xi'an Jiaotong University. 谢宇Xie Yu from Princeton University also serves as a part-time dean at Peking University. These people can change the micro-environment of a research institute or a faculty.

The second method is setting up special academic zones. The leaders of some universities would let returnees who had received talent awards, form a research group and let them decide how to use the money and whom to hire, and in this way stop other officials from interfering with the returnees' work. This could fundamentally solve the problem of bureaucracy in China. Beihang University has such a faculty, so the university is divided into a traditionally-operated half and a special academic zone. The special academic zone thus creates a more flexible academic environment, composed mostly of overseas returnees.

The third method is the double tenure system. The standard is higher for overseas returnees to obtain tenure than it is for domestic PhDs. In fact, the difference is significant. The returnees get paid much more than locals and follow the Western model of six/seven years up or out, which means if an academic doesn't publish enough articles to get promoted in seven years, they will be fired. This is hugely different from the Chinese model of promotion where the faculty member will get paid less but probably get a secure position after nine years. Some locals who want a higher income are willing to comply with the Western model and risk not getting tenure. I know that the Shanghai University of Finance and Economics and the Southwestern University of Finance and Economics have this double tenure system.

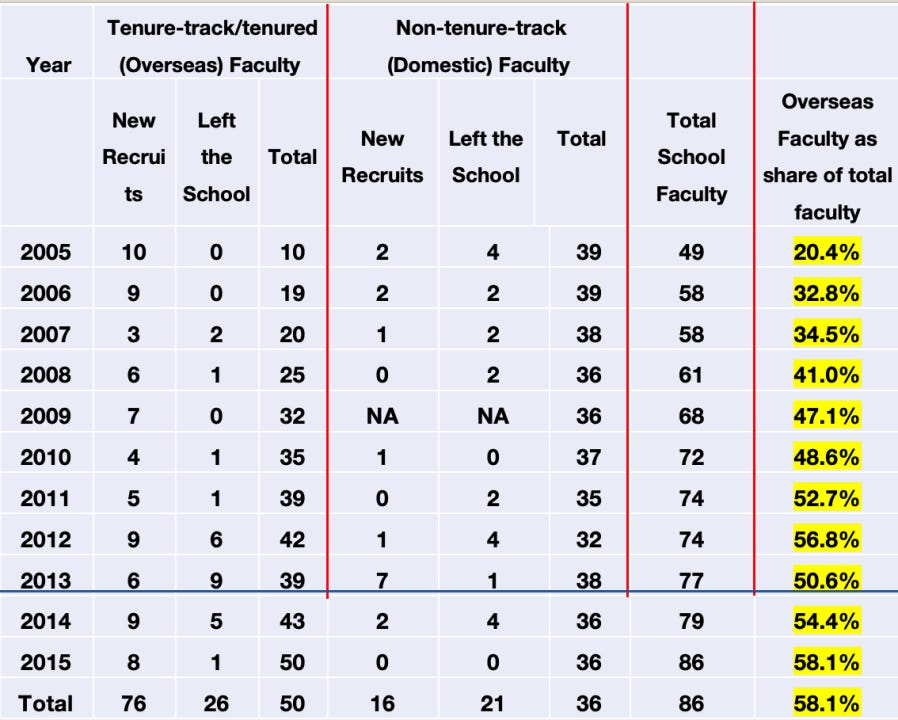

The table below shows how the School of Economics at Shanghai University of Finance and Economics slowly increased the number of returned PhDs in their school in a way that did not create backlash from professors who had not gone abroad.

We did some statistical analysis and found that presidents of universities with overseas PhDs (compared to those with less international experience), or who were brought in as presidents from outside the university, rather than rising within the university, are almost twice as likely to hire other overseas PhDs as faculty members and to carry out the above three types of reforms. That's why I have been closely monitoring whether a university has a president with a foreign Ph.D., or at least has done a postdoc abroad and has been trained in doing rigorous and systematic research for at least two or three years. This is very important for a university.

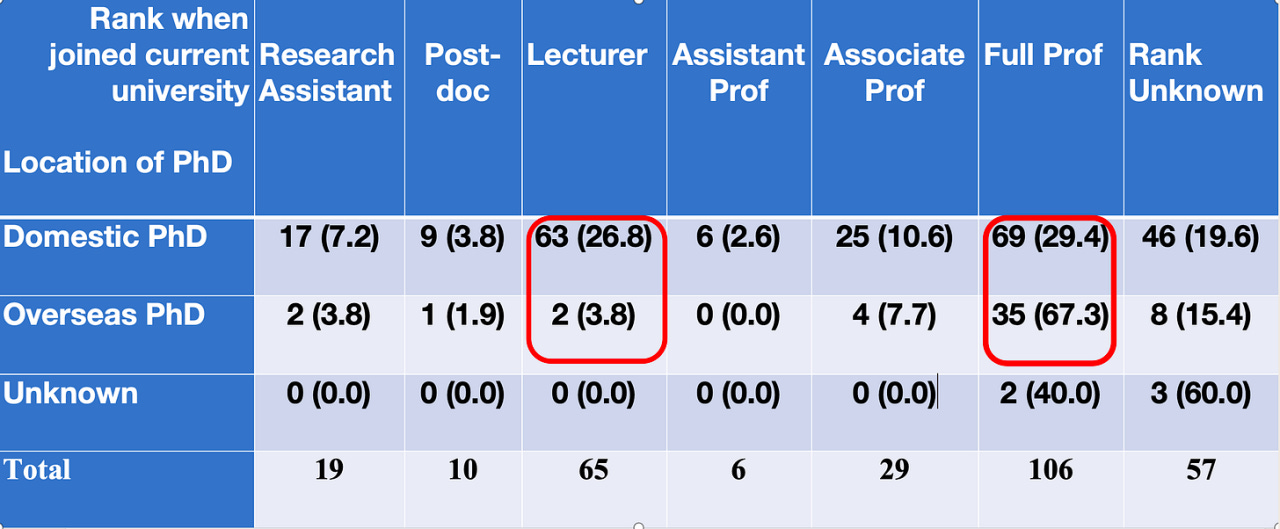

To get people to return, it also helps to promise returnees quick promotions. I have data from 2012 to 2017 looking at those involved in the Chang Jiang Scholars Program. Among those Chang Jiang Scholars, some of them have domestic PhDs, but many got PhDs from abroad. As you can see in this table, 67.3% of PhDs who returned from abroad were immediately promoted to full professor. However, fewer domestic PhDs received a full professor position. This shows that the universities kept their promises to returnees about rapid promotions which can motivate them to return.

Second, back to the scientific institutes. I discovered the shortage theory during my visit to Changchun's Institute of Applied Chemistry at CAS, as I've mentioned before. Many people reported that they went abroad just to look for technology that China didn't have since bringing it back might bring them huge benefits. This shows that overseas returnees also play a significant role in domestic development.

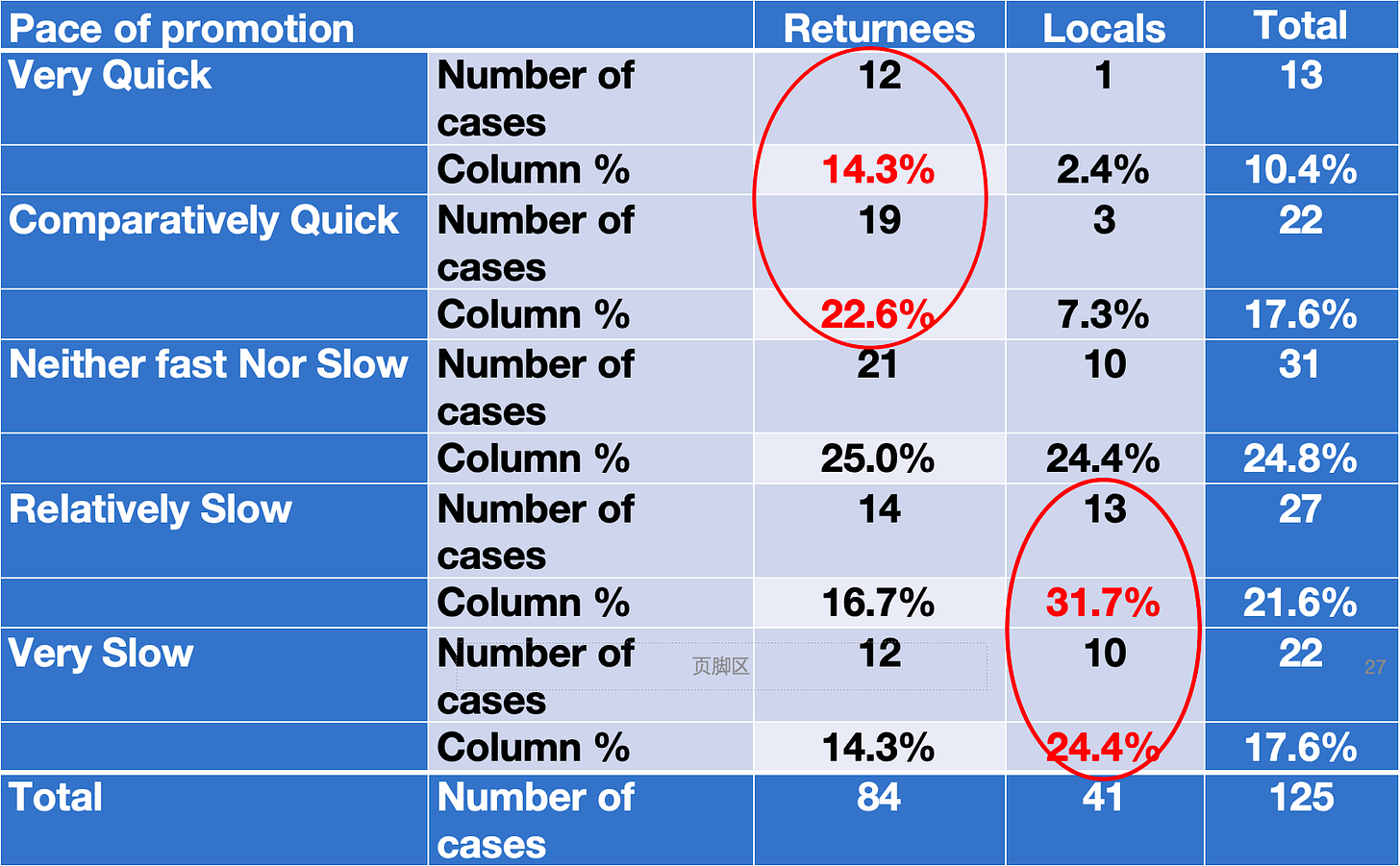

In a study conducted by Chen Changgui and me earlier in 2004, we found that compared with domestic researchers in the CAS, the overseas returnees got promoted more quickly.

So, in the table below, 36.9% of returnees felt they were promoted “very quickly” (14.3%) or “relatively quickly” (22.6%) whereas only 9.7% of Locals felt that way. Similarly, 56.1% of Locals felt that they had been promoted “relatively slowly” (31.7%) or “very slowly” (24.4%), while only 31% of returnees felt that way.

Also, many recipients of the 100 Talents Award at CAS had recently received their PhD overseas and had worked abroad as a post-doc, but when they returned they were suddenly promoted to full professor. I was worried about this, because a PhD student’s doctoral thesis was often their mentor's creation, and their postdoc experience might also have stemmed from their mentor's recommendation. This suggests these people might not be creative enough to conduct new research. Yet all of a sudden, they are at the CAS, running a laboratory, with a considerable sum of funding, and researchers. So we raised our concern that this policy might be a waste of resources. The CAS had a reform then around 2005 and required every professor, principal investigator, and main researcher to be tested every five years to examine the quality of their papers and whether they could open up a new project. And this really matters.

I had some students at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) survey twenty scientific institutes. For each institute, they roughly found twenty people through random sampling and then looked at their resumes which are all available online; this research can be conducted openly. I obtained information on 774 individuals. Analysis of their rate of promotion showed that those with foreign experience rose in status more quickly compared to those who had not gone overseas.

My research also investigated the publication output and impact of scholars who had stayed abroad, but joined a national talent program, and compared it to those who returned fulltime. We found that people who stayed overseas had more impact and were cited more than those who returned fulltime.

Third, about returned entrepreneurs. For entrepreneurs, the most significant change was in the business environment, when Jiang Zemin revised [in 2002] the CPC constitution and allowed capitalists to join the CPC. This reassured overseas entrepreneurs.

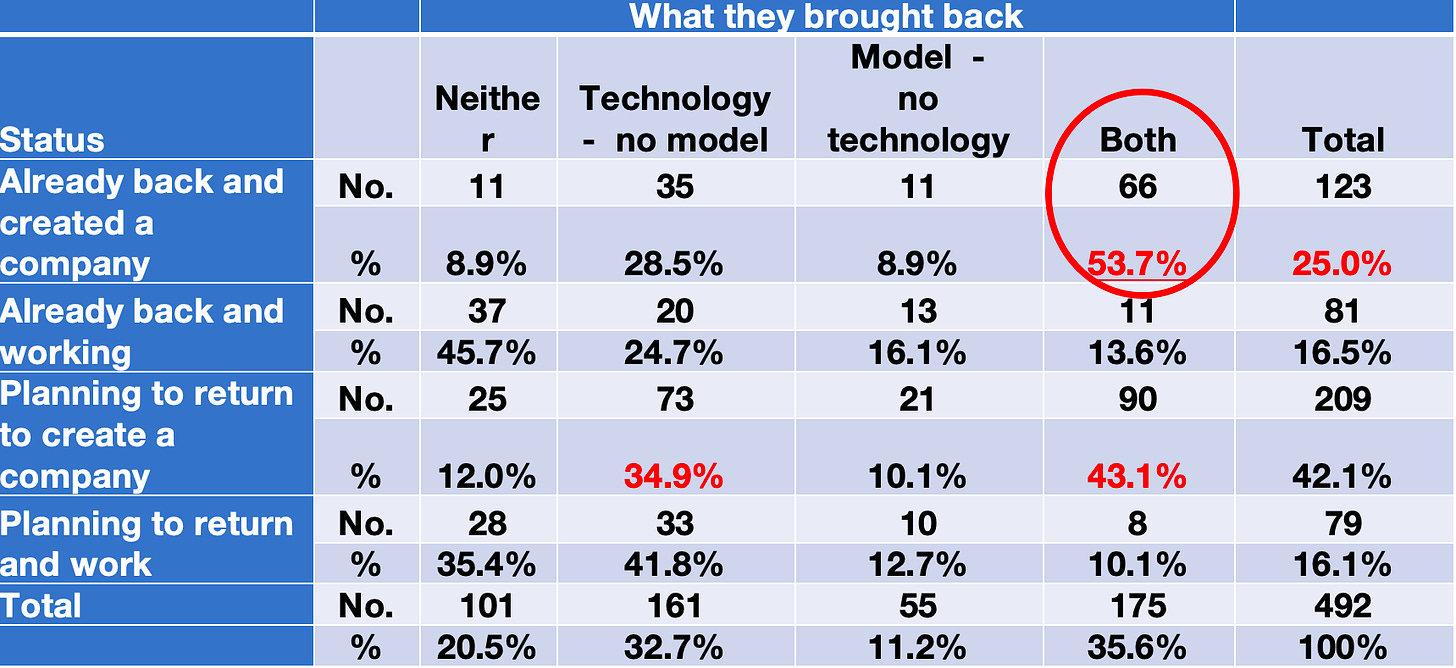

The left column of the table shows the entrepreneurs' backgrounds. Some had already returned and established companies, some already had a job upon returning, some were considering returning to create a company, and some were thinking about returning to work.

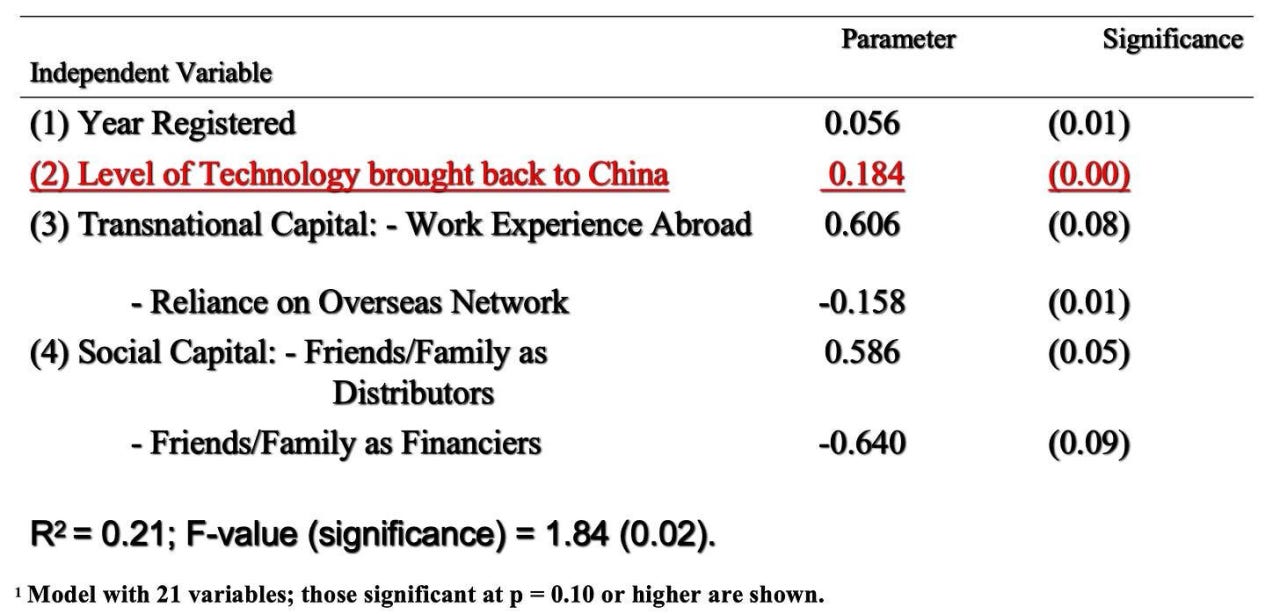

What the returned entrepreneurs brought back is assessed with two criteria: whether they had foreign technology or a foreign management model. We found that most of those who had already returned and created a company possessed both foreign technology and management models, which is crucial.

My 2004 study of entrepreneurs found that the most successful companies are those that brought technology from abroad (level of significance at 0.00). The second most important factor was transnational capital, which refers to work experience abroad. The third factor is the overseas network, which is a negative factor because relying only on your overseas network makes it harder to do business in China So, it is advisable for returned entrepreneurs to bring back foreign technology but to establish good relationships with domestic partners upon their return.

As I said, around 2004, returned entrepreneurs did not necessarily need to bring the most cutting-edge technologies; since China lacked so much technology at that time, bringing second-class technology could still lead to a successful business. However, by 2020-21, "New Tech for China" was not good enough technology for a returnee; 41% of the technologies brought back by overseas returnees were “internationally the latest” because they knew that second-class technology (which was just “new for China”) was not enough. Therefore, the technology returnees study abroad must be the most advanced.

The last topic is about those who returned to work. I believe that many people focus only on those with doctoral degrees or scientists, but in reality, approximately 80% of returnees are those with overseas master's degrees. So more focus should be paid on overseas MAs in China.

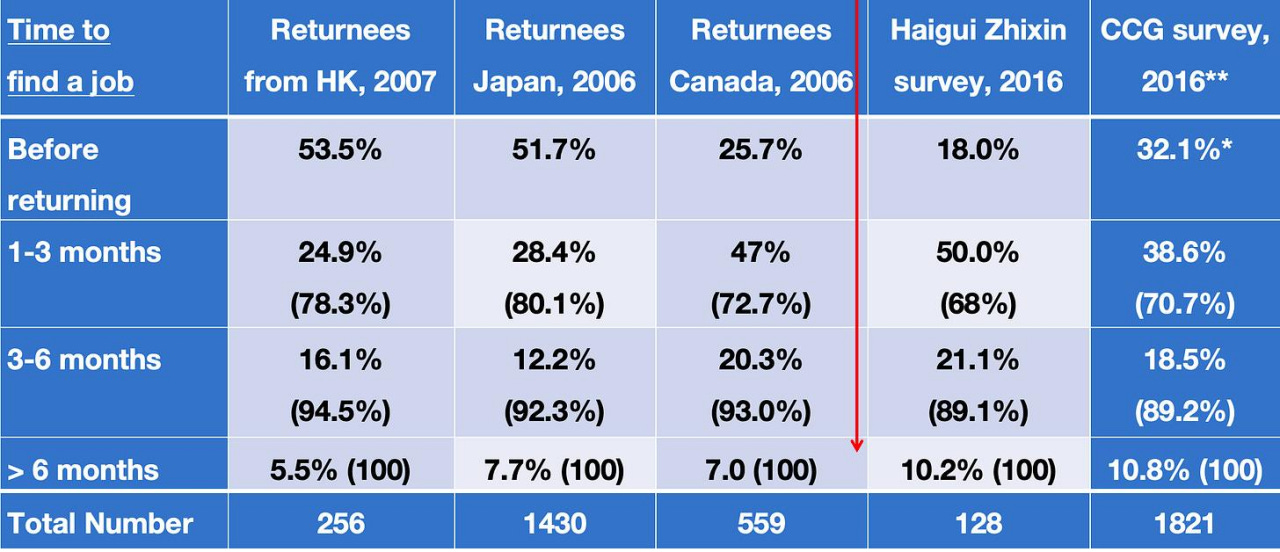

Around 2004, China Daily reported that these overseas MAs couldn't find jobs as easily as those with doctoral degrees. They were referred to as “seaweed” (which is homophonous with "returnees waiting for a job" in Chinese) or "kelp" [as opposed to "sea turtles" which is homophonous with "returnees" in Chinese], implying they were not very valuable. I conducted a study with Han Donglin, and we concluded that the concept of "kelp" doesn't exist. We studied returnees from Hong Kong in 2007, from Japan and Canada in 2006, and the last group, in 2016, which was a collaboration with CCG and Zhaopin.com. These studies show that the majority of people (90%) found jobs within the first six months. According to the standards of the International Labour Organization (ILO), if someone can’t find a job six months after returning, they are considered unemployed. As a result, this shows that the predicament of "seaweed" didn't exist.

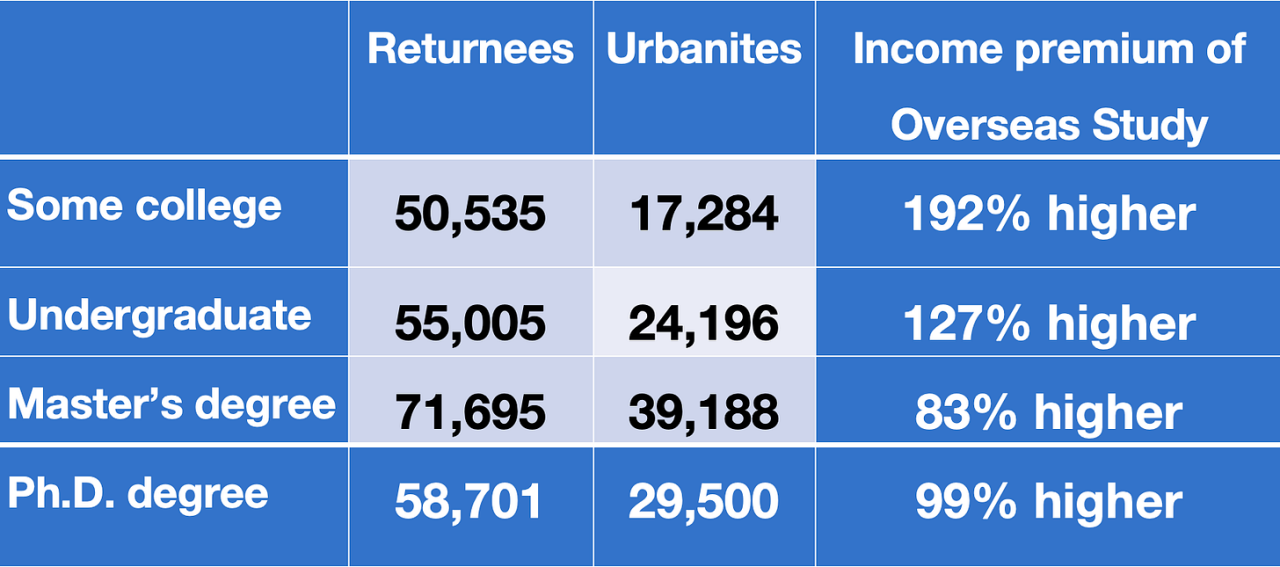

The second aspect I looked into is their income (see table below). From the data in 2006, students with a foreign master's degree got almost double the salaries of those with domestic master's degrees (Urbanites). Those with a foreign PhD also got double the locals. The Southwestern University of Finance and Economics once invited me to participate in their research. They had a large survey sample in 2015, and their main finding was that the wages of people who returned with an overseas master's degree were 19.3% higher than those who didn't go abroad. This figure is not as high as the previous findings in 2006, but the returnees' wages are still higher, suggesting that it is worthwhile to study abroad.

I plan to publish a book next summer titled "The War for Chinese Talent in America,”, describing how the Chinese government incentivized Chinese students studying overseas and Chinese scholars working overseas to bring back their technology and human talent to China, without necessarily returning to China. However, as the book discusses, the U.S. government was not so happy about so much technology being transferred, so it has tried to stop that process from occurring.

I've been studying returnees for 32 years, whether they stay abroad or return to China. I've traveled to many cities, been supported by many friends, and communicated with countless people. I've conducted about 15 social surveys. I've also made some suggestions and reports to the Chinese government, to the Organization Department of the CPC Beijing Committee, and to the Organization Department of the CPC Central Committee. This is the work of a lifetime. I totally understand the desire of the Chinese people and the Chinese government to increase the quality of its technology. But I am also aware of the importance of dialogue between the U.S. and China, to resolve some of the misunderstandings, especially regarding the roles of students who study abroad and the Chinese professors who remain abroad. I know this is also the mission of CCG, and we must open the floor for dialogue. Thank you.

Other lectures at CCG