Beyond trade diversion: the path to diagonal reciprocal cooperation

Part II of lecture by Chief Economist of the East Asia and Pacific Region of the World Bank at CCG

Hi, this is Yuxuan Jia from Bejing. This is the second and concluding part of Aaditya Mattoo's lecture at the Center for China & Globalization (CCG) on January 17, 2024, themed "The New Protectionism: Origins, Implication, and Remedies." The first part of Dr. Mattoo's speech has already been published and his dialogue with CCG Vice President Mike Liu will be released shortly.

Aaditya Mattoo's lecture, in this segment, illustrates how nations such as Vietnam, Korea, and Thailand are capturing a larger share of the U.S. market, even as Chin’s share of the US market declines. This shift serves as a textbook example of trade diversion, a consequence of the reciprocal protection policies implemented by the US and China.

Nevertheless, despite efforts to diversify trade away from China, there's a noticeable increase in indirect dependence. This is evidenced by countries increasingly importing inputs from China for the production of exports to the U.S., creating a complex web of triangular trade. This phenomenon underscores the subtle yet profound interdependencies that define the global economic system.

To conclude, Dr. Mattoo underscores the vital importance of international cooperation in areas extending beyond traditional trade concerns, such as taxation, regulation and anti-monopoly regulations. His emphasis on these broader issues is pivotal for a comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted nature of trade and the necessity for holistic policy strategies in navigating the future of global commerce.

Aaditya Mattoo is Chief Economist of the East Asia and Pacific Region of the World Bank. He is also Co-Director of the World Development Report 2020 on Global Value Chains. Prior to this, he was the Research Manager, Trade and Integration, at the World Bank. Before he joined the Bank, Mr. Mattoo was Economic Counsellor at the World Trade Organization and taught economics at the University of Sussex and Churchill College, Cambridge University. He holds a Ph.D. in Economics from the University of Cambridge and an M.Phil in Economics from the University of Oxford.

The event was covered by domestic news outlets including China Daily, Economic Daily under the Publicity Department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC), International Business Daily under the Ministry of Commerce of China, Beijing Daily, Phoenix TV, China Radio International (CRI) under China Media Group, and China’s Diplomacy in the New Era under China International Communications Group.

The full English and Chinese videos are available on CCG’s official WeChat blog. It is also accessible on YouTube.

***Following the publication of our article, Mr. Mattoo graciously reached out to us with suggested amendments for lexical accuracy, without altering the original perspectives. In response to this constructive feedback, we updated our publication with the revised content provided by Mr. Mattoo, ensuring the most scientific rigor and precision of the narrative.

— Yuxuan Jia, 11 March***

Let me just give you a little bit of evidence on the implications of why and what is happening because of the increase in reciprocal protection in the US-China trade relationship. Other countries are increasing their share in the U.S. Market. For example, Vietnam, Korea, and Thailand have increased their share in the U.S. market and China’s share in the U.S. market declined significantly. Also some countries like Indonesia and China have increased their share in the Chinese market. The U.S. share has declined, but the share of some other countries like Japan and Korea has also declined they are upstream from China in global value chains – i.e. they provide inputs used by China in its exports to the US. So there is trade diversion but also other effects because of production linkages.

Second is the impact of measures like the recent US Inflation Reduction Act. Until there were new tariffs only on China, other East Asian countries were able to expand. But the IRA adversely affected the exports of other ASEAN countries. This is because now the requirements were that you had to be part of certain free trade agreements with the U.S., otherwise your products would not eligible to meet the local content requirements as condition for access to the IRA subsidies.

So you saw a decline in the share also of other ASEAN countries due to the introduction of the new IRA measures.

It is interesting to see what factors can help understand the change in sources of imports. And you see it is not only based on economic considerations, but also linked to political considerations. For example, it is not just based on the tariffs faced by exporters, but also whether you vote similarly with the U.S. at the UN. So there is sign of politicization of trade, which does mean that trade is not strictly based on the economy, but also on other factors which are less easy to negotiate.

Then there is also an interesting phenomenon of indirect dependence. In the U.S. market, we have a decline in China share of final good imports because China faces higher tariffs. You see an increase in the share of other South East Asian countries like Vietnam in the U.S. market. This is what you’d expect. But what is interesting is you also see an increase in the share of imports from China in Vietnam. What does this mean?

If you look at this next picture, it will help you to see. When other countries want to export to the U.S. to take the place of China, they import more inputs from China. So an interesting pattern of triangular trade is emerging. The dependence on China is still very strong. The direct dependence has been reduced, but it has been replaced by indirect dependence. In this deeply globalized world, you cannot easily decouple. You can only gradually change the nature of relationships.

This next picture shows the association between the growth in exports to the U.S. and growth in imports from China for countries across the world. This positive relationship tells you that the countries which increased the exports to the U.S. also saw an increase in imports from China.

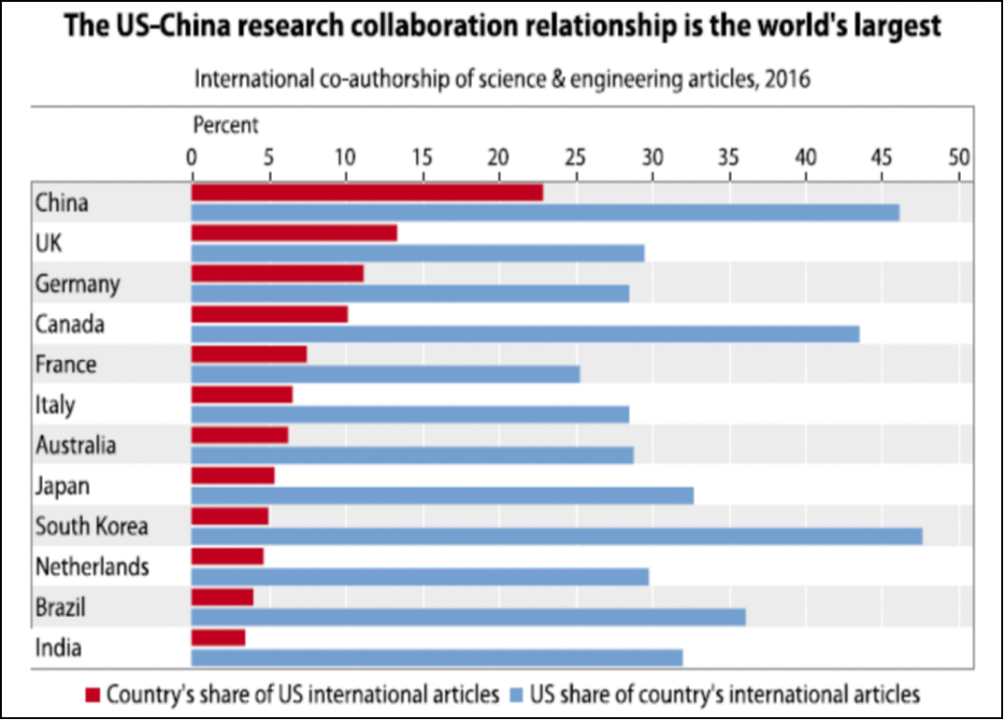

Beyond trade, some of the most important research relationships are between the U.S. and China and the world, in the ways that that individuals collaborate, in the way that research builds on the research of others.

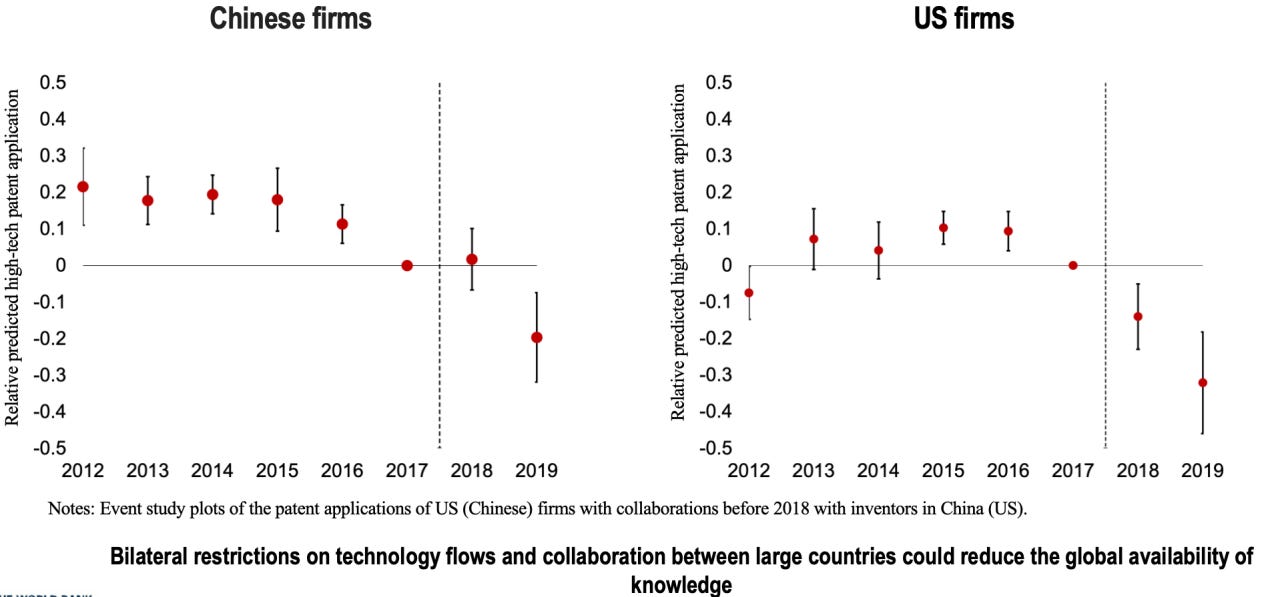

There is evidence that the mutual restrictions have led to a reduction in innovation by Chinese firms which used to collaborate with U.S. firms, and also a reduction in innovation by U.S. firms which collaborated with Chinese firms. These restrictions are hurting innovation in both the U.S. and China. And that matters for the rest of the world, which relies on that knowledge.

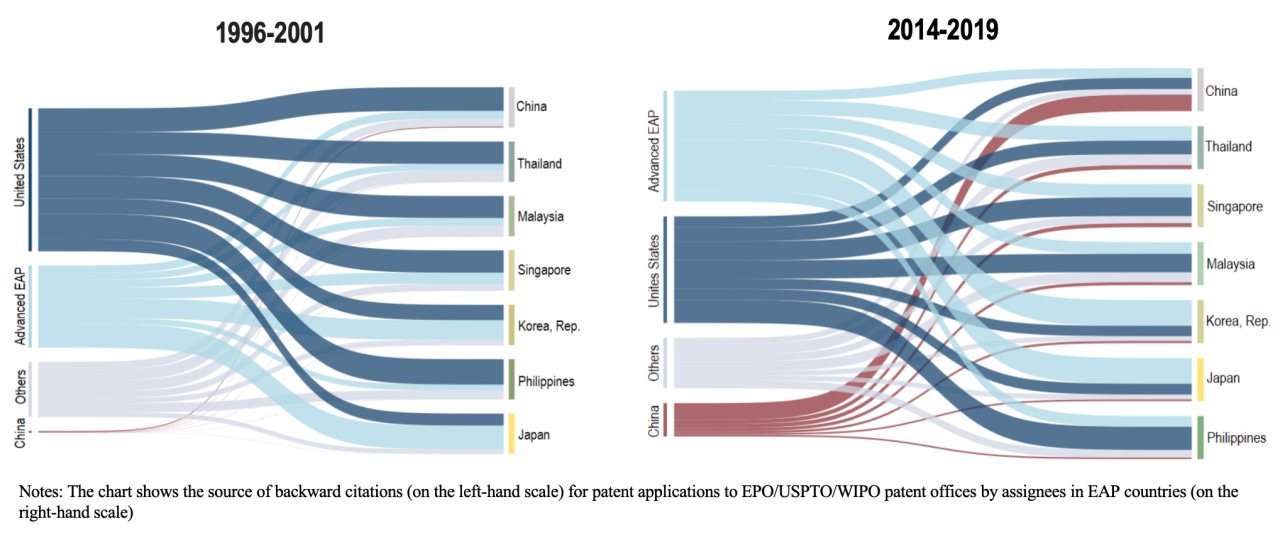

This is a picture that shows how much other countries in the region depend on external knowledge flows. You see the knowledge dependence used to be a lot on the U.S. and relatively little from China. Now, the dependence is still a lot from the U.S. and advanced countries, but it has also increased from China. When you have mutual restrictions which reduce the flow of knowledge, they are going to affect the whole world. For example, we are trying to deal with climate change. And one of the biggest challenges is to create new technologies which can lead to efficient green production. But some of these mutual restrictions will make it a little bit harder.

Let me just conclude by saying a few things about how we can deal with this problem, and I think there are two broad ideas.

One is that to keep trade open, we need to cooperate beyond trade. I gave you an example of how hard it is to help the losers because you can’t tax the winners. One obvious solution is to cooperate on taxes. This is what is happening at the OECD. The world is beginning to say, "Let’s agree on a minimum tax because that is a way of empowering the government to help those who lose. And if you can do that, you don’t need to use trade restricting policies. You can continue to keep trade open and beneficial."

There are also big questions regarding preserving competitive conditions and dealing with monopolies. For example, one of the big problems is when monopolies exploit consumers in another country. It’s also a problem when a country itself imposes an export restriction- which is also an exercise in monopoly power. Supposing you have a monopoly on semiconductors, or you have a monopoly on essential minerals. The risk of such restrictions also legitimizes protection, because a country can say “I need to develop my own industry because I cannot be sure that someday in the future you will not shut me out.” It is not efficient if everybody tries to develop their own industries. But unless you can provide a guarantee that in the future you will not suddenly be shut out, there is no obvious solution to the problem.

Another problem concerns regulation of international market failures. For example, consider when data flows from one jurisdiction to another, say from the EU to China so that Chinese firms can provide data processing services. How can China credibly reassure the Europeans that it will protect their privacy to European standards? Because if you can’t do that, that data will not flow. And data is today the lifeblood of the global economy.

Similarly, concerning the environment, suppose the EU imposes a significant carbon tax, but China imposes nothing. That creates pressure on the European governments because their industry says, “We cannot compete with other countries which are not imposing the same tax. We need at least to impose a carbon tariff on the border.” But if the source country also takes measures to mitigate emissions, then there is less reason for the destination country to take action.

The key idea is that to keep markets open in each of these cases, you need to deal with international market failures, arising from monopolies, asymmetric information, externalities. The history of trade cooperation has been “you open your market, I’ll open my market” – reciprocal liberalization of import restrictions. Sometimes, groups of countries have tried to go further. For example, in Europe you see efforts to harmonize or mutually recognize regulation. “You recognize my doctors and my banks, and I will recognize your doctors and your banks, so we can provide the service to each other.” Even that has not made a lot of progress, because countries with different histories, objectives and standards are unwilling to harmonize even to the limited extent needed for mutual recognition.

My proposal is we need to change the way we think about negotiation. I would like to propose “diagonal” negotiations, in which a country that exports promises a country that imports that it will protect its interests. If my bank goes to your country, I will make sure that it does not default on your consumers. If your data comes to my country, I promise you it will be treated carefully. If you buy from me, I will not tomorrow shut off my exports. These are not reciprocal liberalization but exporter guarantees that are designed to persuade the importer not to protect their markets.

Consider a concrete example: data flows between Europe and the U.S.. The European Court of Justice said “Our data cannot go to the U.S. because U.S. regulation and firms do not adhere to the stands of privacy that prevail in the EU.”? The US firms solved the problem by negotiating an arrangement that was called the “Safe Harbor” and then became the Privacy Shield. This was a promise by American companies to protect the data of European citizens to European standards because American standards were not sufficiently strong and there was not yet a political consensus in the US in favor strengthening national standards. It was that promise which allowed the data to flow: the exporting country making a promise to the importing country that “if you let me process your data, I will in return protect your citizens privacy and security.”

Another example is of state enterprises, where a foreign country is worried that a firm in one country is too close to the government, that it will not act purely like a commercial firm but in a strategic way. The foreign country may say, “I’m not going to let you invest in or build my telecommunication infrastructure because you’re too close to your government.” I think the only solution to this is some kind of commitment that the government will not influence the enterprises. If you can make that commitment credibly, you will open the foreign market. If you cannot make that commitment or you do not want to make that commitment, then you lend legitimacy to the foreign restriction.

I believe that negotiating these “diagonal” commitments across different areas - climate policy, regulatory policy on data and on competition - is going to be the heart of the future liberalization negotiations.

Let me make the final point now. All countries, including China, face the choice. The multilateral trading negotiations have stalled, but there are other types of negotiation. RCEP was concluded and China has applied to join the CPTPP. There are different agreements. What should countries do now? One general principle is that for a third country, [if] two large countries start distancing themselves from each other, it is better to form agreements with both countries. Not join one club, but be a member of all clubs. Because then you become the “hub” rather than a “spoke.”

But particularly from China’s point of view, I think it is important to recognize that there is still a very large part of the world which wants openness, which wants freer trade. One implication is that it would make sense for China to make the kinds of commitments that are in China’s own interest and also serve to reassure other countries - whether it’s on protecting data, arm’s length relationships with the state, and the behavior of state-linked enterprises. I think this is a way of ensuring continued openness to foreign trade and investment in a way that is in China’s interest. Because it wants access to foreign markets, and it also wants investment. Because that’s how China’s growth has happened and how it will continue.

A second implication is that China can through its own liberalization and reform, which have delivered big improvements in living standards, can also increase the stake of other countries and other companies in the Chinese market. And that can change the political economy in other countries. Even in other countries which are restricting trade with China, there are some who say, “We must protect regardless” and others who say “We want to sell to Chinese who have a growing market and we want to buy from Chinese who are a really efficient source.” That latter group of people becomes politically stronger when China’s market is open and predictable.

To conclude, I think this is an important opportunity for China to shape the global narrative on international cooperation. That would also be consistent with China’s growing importance in trade. And that’s why I showed you the long historical picture. As you become more dominant, it is in your interest to assume greater responsibility to preserve the rule-based trading system. Because then you can promise to play by the rules and will not, for some other political reason, suddenly switch off the tap or impose restrictions. That reassures your trading partners and ensures they continue their economic engagement with you in a way that is mutually beneficial. I think believe that taking a long and broad view along these lines is much more in China’s interests than to be trapped in narrow and myopic trade conflicts. I hope very much that you find these arguments at least interesting! Thank you.